Picture a typical commuter train carriage this week. Someone is probably reading the news on their phone. Someone else might be watching video on a laptop or using an app on a tablet. Another might be publishing their latest snippet on Twitter or sending a message to the BBC correspondent whose report they have just read. There might even be someone reading a newspaper.

We take all this explosive expansion in our media habits for granted – to the extent that there is nearly a middle-class riot if the BlackBerry servers go down for a couple of days.

Our relationship with content has been revolutionised. Not just in the sophistication of the devices we use for consuming it, but in the blurring of the lines between professional and amateur content producer, between broadcaster and publisher, and between reporting and reaction.

It’s not that long ago that media-owners would routinely describe themselves as newspaper or magazine publishers, or as broadcasters. They would define themselves by the product they produced. Only gradually did they begin to talk about owning content ‘brands’ – after discovering they could make money out of ‘brand extensions’ like events, and online activities.

But in this multi-channel world, publishers are no longer certain what their identity is. If they are no longer defined by their products, and content is no longer the sole province of the professional producer, and if consumers are increasingly turning to their social networks for information and entertainment, then what are they for?

In the old days, the business model was simple. Content generally meant journalism, commissioned by an editor. People paid for that content, and advertisers paid to reach those people by nestling their promotional messages within the comforting environment of well-crafted editorial.

Publishers still had full control over the fundamentals of their business – content, pricing, distribution, and format. They owned the channel, and ‘their’ circulation. Competition meant other publishers, rather than unpaid bloggers, public bodies, Twitter feeds, search engines and social media groups.

As anyone will now tell you, this business model is not so much broken as disintegrated.

Unfortunately, too many publishers are still looking inwardly at their own products and brands, and relying on technology alone to provide the solution - rather than putting the customer at the heart of their business strategy.

They are terrified of falling behind the curve if they fail to adopt the latest format, but uncertain as to how to make money from it, and reluctant to let go of older revenue models. And they are not sure whether tech companies, social networks and content curators are friend, foe or ‘frenemy’.

The risk is that in remaining rigidly product-focused, they attempt to stitch together a new business strategy from a collection of random tactics. They try out ever more ‘creative’ solutions to whet the appetite of jaded advertisers who have less money to spend on more options – many of which no longer involve traditional media owners at all. They juggle a dozen formats and iterations of their brand – each sucking up resource and management time for ever more slender margins, which they attempt to offset by cutting back on cost – not just on print and repro, but on content creation. And so the decline continues.

To avoid this downward spiral, the task of re-inventing the publishing business model needs to start not with the product, or even with the content - but with the consumer.

Audience first

At its heart, every publishing business is based on a single vital asset – a relationship with a community. This community used to be known as ‘readers’, a term which now seems rather quaint. Now we are perhaps more likely to use the term ‘audience’.

It is this relationship which is monetised through a simple business model which drives two sources of revenue. If the community values your content highly enough, they will pay for it. And if advertisers want to reach that community badly enough, they will pay to do so. The first of these revenue streams requires the creation of value in the content that is delivered. The second relies on bringing buyers and sellers together effectively.

Ultimately though, it is the relationship with the audience which is key. The brand simply signifies a certain set of quality and content expectations to that audience. The products provided by that brand (whether print, digital, video or live events) are no more than a set of channels for conveying content to that audience in the most appropriate way.

So, while continual experimentation with new formats is inevitable and necessary, the more fundamental shift required by publishers is to move from a product-based to a customer-focused content strategy.

Understand your audience first, so that you can make sure you produce the content they want. Then deliver that content in the way that is best suited both to the audience’s needs and the dynamics of the content itself. Audience first, content second, and format third – rather than the other way around.

Understanding your audience

So how much do you really know about your audience?

There are three main strands to this task: what you can find out about their information needs; the behavioural data you gather as they use your content and services; and the details you can collect about them as customers.

If you are a specialist publisher, you might feel that you know your audience well. Chances are that your team prides itself on being immersed in the sector they report on. You probably conduct regular ‘reader’ or audience surveys in order to check what they think of your output, how well you stand up against the competition, what they would like more or less of. But as research goes, this is the equivalent of looking in the mirror. It tells you something about yourself and your appearance to others, but precious little about your intended audience.

To understand their information needs in depth, you need to ask them about themselves, not about what they think of you. What information do they need and use in their daily lives, where do they find it and how do they use it? What do they pay for it? What format would they like to receive it in?

To avoid navel-gazing, don’t restrict it to the kind of information you happen to produce at present. Probe deeper. What information do they really value? Where do they get it from currently, what other info would really help them that is either not available, or too hard to find? It may not be journalistic in origin. It may not even be word-based.

If you can start to discover what these deep needs are, you can begin to tailor your content strategy to what they feel they ‘must have’ (and would be willing to pay for) rather than a further refinement of what you have always provided them.

Understanding the numbers

When it comes to understanding audience behaviour, we now have access to more statistics than we know what to do with. But it’s becoming clear that the real answers are to be found in the detail – the old currencies of circulation or page impression figures are increasingly irrelevant.

I once sat through a presentation from the editor of a B2B title. It was an unashamedly ‘trade’ title covering an industrial sector – a cracking read for those in that business, but a chortlingly obscure title to Joe Public. The editor duly put up the obligatory graph of page impressions to illustrate the performance of his website, which revealed a spike in traffic in one particular week which was so huge that it looked like an aberration.

What incredible front page scoop had so electrified the web-surfing public? It turns out it was a trifling down page diary item, which had wryly recounted how the mag’s own set of awards had been inadvertently gatecrashed by all five members of Girls Aloud (who had stumbled down the wrong corridor in Grosvenor House from a music industry event next door).

So the traffic spike was caused not by people eager to learn about the editor’s finely-honed opinions on the latest advances in widget engineering, but by girl band aficionados Googling the name of their favourite group. Imagine their excitement when they landed on his news page instead of the latest celebrito-gossip blog.

There was of course no value to the title in this massive traffic boost. These accidental visitors were never going to pay for its content, nor were its advertisers remotely interested in paying to reach them. Dropping Cheryl Cole’s name into other pieces about widgets on a regular basis might have lifted traffic figures, but to what end? It’s not the quantity of eyeballs that matters, it’s the quality.

So audience-chasing alone is not the answer. A more sophisticated approach is required.

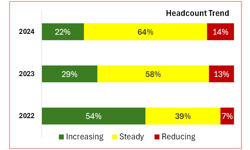

In an increasingly data-driven world, it is greater engagement from your audience that will lead to greater rewards. But how do you measure it? The more salient measures are frequency and duration of visits, downloads, comments posted, items shared or ‘liked’, registration details given or purchases made, and click-through rates. These are the measures which indicate your content is not just being looked at, but is valued and used.

They not only provide vital feedback which will help to improve and refine your content and product strategy, but will give some much needed heft to your ad sales story. And by providing real-time information on audience interests, they also aid lead-generation.

Tesco Clubcard is often cited as the uber-role model for how to use data about shopping habits to build information about customers - not only trends, but specific information sets which can be used for targeted marketing efforts.

On a smaller scale, publishers also have an opportunity to gather information based on how their audiences and subscribers interact with their content – a continual live lab in which to measure and tweak their content strategy, and adjust pricing strategies. Coupled with the personal information volunteered by users, this could become a powerful commercial tool.

Turning audiences into customers

In moving from a product-focused to a customer-centric strategy, publishers will also have to become a lot more adept at joining up the customer data that they hold across all different iterations of the brand.

Broadly speaking, people just want to have their information needs met – rather than amassing an unwieldy collection of individual content products. Simplicity is key. If you are going to serve the customer effectively across multiple platforms, then they will need to be able to move seamlessly from one to the other without stumbling through multiple logins and subscriber IDs.

More importantly, if you are going to exploit the opportunity to up-sell them to other products and content streams, then a coherent set of customer data is essential. Your overriding aim is to increase the yield per customer, rather than the sales of a particular product.

But how do you square the circle between building a vibrant, high traffic community on the one hand and creating a high value information service which sits behind a paywall? Going back to our business model, is it still possible to have both strong ad revenues and good content revenues?

The short answer is yes. But when it comes to persuading people to pay, not all content is equal. Where does the value lie, and how do you adjust your output accordingly? Have you got the right mix of content and skills in-house to make it happen? Can you make 'content curation' pay, and how do you unlock the value in your existing content?

In part 2, I will explore the second stage of the process of developing a winning content strategy – the content itself.

Stephen’s ‘How to develop a winning content strategy’ series:

Part 1: Audience (Nov/Dec 2011)

Part 2: Content (Jan/Feb 2012)

Part 3: Format (Mar/Apr 2012)