Mary Ann Sieghart won a scholarship to Oxford when she was sixteen and got a first in Philosophy, Politics and Economics.

She could have chosen many careers – but only one was ever going to do.

“I have always wanted to be a journalist, since I was about twelve. I wanted to be either a political columnist or editor of The Times,” she remembers.

“I got one of them so I am not complaining,” says Sieghart whose roles at The Times across nearly twenty years also included being arts editor, chief political leader writer and acting editor of the Monday paper.

“I have always been fascinated by news and I wanted to be in the thick of it. I always wanted to do political journalism not just journalism,” adds Sieghart who has pursued a portfolio career since leaving The Times.

It has ranged from being on the content board of communications regulator Ofcom and being a member of the Tate Modern Council to presenting a range of BBC Radio 4 programmes such as Start The Week and Analysis.

Sieghart is a non-executive director of the Guardian Media Group and a visiting professor at King’s College London.

Yet, until recently, there was one big gap in the list of ambitions fulfilled. She has never managed to complete the writing of a book even though she felt her political columns gave her something of the status of a published author.

It niggled because generations of her family had written books, including her father Paul, a human rights lawyer whose publications included the prescient ‘Privacy and Computers’, published in 1976.

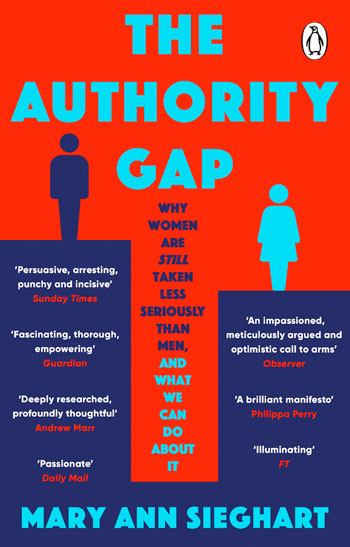

As she entered her late 50s, Mary Ann Sieghart decided the time had come and she had an idea, although there was no Eureka moment. The result was a bestseller: The Authority Gap: Why women are still taken less seriously than men, and what we can do about it.

The theme was sparked by the fact that Sieghart had noticed the phenomenon all the way through her life – not least in her career in the media – as had women around her. She had even written columns about aspects of the issue.

“No-one had put a name to the phenomenon nor had they written a book that pulled together all the research evidence for it, of which there was one hell of a lot,” explains Sieghart.

The story of their lives

Every woman she spoke to in researching the book, however distinguished, punched the air in delight and said it had been the story of their lives, although men tended, unsurprisingly, to be more sceptical.

Everywhere she looked, she found more academic studies on how women, however highly qualified, were routinely disadvantaged compared with men. The devastating findings were scattered across a variety of academic disciplines from social psychology and gender studies to business, management and economics.

It took a sharp journalistic eye to pull it all together and tell the bigger story.

Sieghart accepts that in her career, she was usually treated with respect because of the authority conferred by a byline column in The Times – if people knew who she was. If they did not, it was a different story.

She tells of attending a conference where she was talking to a former head of the Foreign Office and a BBC foreign correspondent when an Italian delegate asked them whether Tony Blair could make a comeback.

They deferred to Sieghart who explained that there was absolutely no chance of such a thing happening.

The Italian then directed his follow-up questions to the two men and completely ignored Sieghart.

“He thought they knew more than me even when I proved I knew more than them,” she added.

From her days at The Times, Sieghart remembers having two talented deputies, Michael Gove and Matthew d’Ancona.

“Both of them just leapfrogged me. They are both brilliant men but it looked like a bit of a pattern,” notes Sieghart who was invited to one of Rupert Murdoch’s biennial international conferences bringing together News Corp’s top executives.

Only three of the 50 speakers were women and the three included Murdoch’s daughter, Elizabeth.

Sieghart was also treated to a column in Private Eye called Mary Ann Bighead, a parody aimed at her, something she found hurtful, particularly when they called her two daughters, who were still at school then, Brainella and Intelligensia.

“I didn’t think I was that big headed, certainly not as big headed as most of my male colleagues. It was basically, women, know your place,” says Sieghart.

Was she ever a serious candidate for fulfilling the other half of her ambition – becoming editor of The Times?

“I thought it was possible but clearly Rupert didn’t,” says Sieghart who notes she made no secret of her ambition.

She concedes she was probably ideologically too liberal and too establishment a figure for Murdoch’s taste.

Sieghart concedes she also didn’t do her promotion chances much good by suggesting a management buy-out of The Times to Murdoch, arguing that The Independent was then doing so much better than The Times because it was independent of proprietors.

Male dominated

When she first began editing the opinion pages of The Times in 1988, she inherited eighteen columnists across the week and all were male. She had to fight to get the first woman, Libby Purves, appointed. Even by 2020, Sieghart notes that five out of the six lead columnists on The Times were still men.

“What does that tell us about how seriously we take women’s opinions compared to men,” she asks.

Sieghart accepts she was relatively privileged compared with the “pretty ghastly” position of most women journalists at the time working in testosterone-fuelled national newspaper newsrooms.

From her days in political journalism, two stories stand out: One she wrote and another she didn’t.

The most stressful one was breaking the story of the alcoholism of the then Lib-Dem leader Charles Kennedy, a condition that was well known but had not been publicly disclosed.

After discovering how badly Kennedy’s drinking was impacting his party, including being unable to reply to a budget speech because he was too hung over, Sieghart published chapter and verse.

He tried to sue because it was very close to an election campaign and in the end, The Times, according to Sieghart “slightly cravenly”, published not a correction but a clarification over something fudged to protect a source.

“It was a shame because I really liked him,” she notes now.

Former Conservative leadership candidate Michael Portillo, and his gay behaviour at Cambridge was the one that got away.

Over an off-the-record lunch, Portillo detailed his university experiences and Sieghart, who thought it was nice that he trusted her with such personal and controversial information, never told a soul.

Six months later, Ginny Dougary, also of The Times interviewed Portillo and he detailed his Cambridge experiences on the record.

It caused a sensation and helped Dougary win a British Press award.

In a lesson to all journalists in such tricky situations, Sieghart now says that had she been a better journalist, she should have gone to him after the lunch with an offer to write something if that was what he wanted, which he probably did.

Seeing it from both sides

The Authority Gap is a detailed compendium of the myriad ways in which men put down women, sometimes instinctively and unconsciously, from across the world.

Should you seek evidence, none is more unanswerable than the experiences of men who have transitioned to women and vice vera – in this case from the world of science.

Distinguished men, when they started living as women suddenly found their work downplayed and overlooked. Women who transitioned to men, almost overnight found their opinions were sought and their work was taken far more seriously.

When Ben Barres, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then living as a woman, solved a complex series of mathematical problems, his professor commented: “You must have had your boyfriend solve it.”

Later as a middle age male neuroscience professor, Barres couldn’t believe how much more seriously his work was taken.

Sieghart tells how a faculty member who didn’t know his story, commented that his work was much better than that of his sister.

The Authority Gap has been published in America, Brazil and South Korea, so far, and Sieghart has found that many people buy copies for others.

“Just today, someone told me she had bought seven copies for the male members of her executive team,” says Sieghart.

On a personal note, my daughter Julia bought copies for all the men in her family for Christmas.

But surely, at least in British journalism, things have rapidly begun to improve with female editors at The Daily Mirror, The Sun, The Guardian and the Financial Times, and until recently the Sunday Times although Emma Tucker is moving on to become the first female editor-in-chief of the Wall Street Journal?

“Things have got quite a bit better. The number of women editing national newspapers has really changed,” says Sieghart who believes it is amazing what a difference having a female editor makes.

At The Guardian, edited by Katharine Viner, the gender balance on the opinion pages is roughly 50-50. At the FT, edited by Roula Khalaf there is a bot which measures the balance of female and male experts quoted in stories.

Women leaders, not just editors, she argues, tend to be more inclusive, more collegiate and often more effective.

For Helle Thorning-Schmidt, a former Danish Prime Minister, the test of true equality will be very clear.

She believes we will know it has been achieved when there are as many mediocre women as mediocre men in positions of power.

Sieghart is already planning two new books but she will still have to go some to match the achievements of her late mother Felicity Ann.

At the age of 76, she hit two holes in one in a single round of golf, managed the Aldeburgh Cinema for years despite having no previous experience and learned to play bridge in her eighties.

Mary Ann Sieghart is only 62.

‘The Authority Gap: Why women are still taken less seriously than men, and what we can do about it’, by Mary Ann Sieghart, is published by Penguin Books.

This article was first published in InPublishing magazine. If you would like to be added to the free mailing list to receive the magazine, please register here.