A shadowy woodland appears from time to time on the edge of Fleet Street. Black-trunked trees with grey canopies – venerable trees, some gnarled and bent by the elements, others tall and upright in defiance of the years – move slowly, like Malcolm’s Dunsinane, to form a thicket in St Bride’s church and pay homage to a once mighty oak that has fallen.

The copse then shuffles on to recongregate somewhere the trees can absorb nutrients, spread their branches and recall the days of the great forest before dispersing – until the next time. This ritual is called the memorial service.

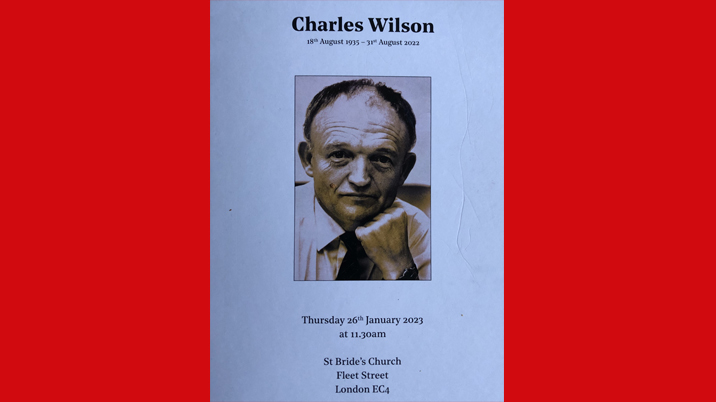

The trees – grey-haired journalists in dark woollen coats – were on the move again yesterday morning to remember one of the great characters of late 20th century journalism: the former Times editor Charlie Wilson. They were joined, among others, by four other occupants of the Times chair, alpha male combatants Piers Morgan and Alastair Campbell, the playwright Tom Stoppard and the TV executive Elisabeth Murdoch. And, of course, the family: three wives, three children and seven amazingly well-behaved grandchildren, who must have spent most of the afternoon wondering how much more of this bonus day off school would be lost while the old hacks swapped ailments and misremembered anecdotes about how great they had once been.

How much of an ordeal must these occasions be for the families. There is the distance of time from the death, but not so much that the raw grief does not return to the surface. It is supposed to be a celebration of a life, but this may well be a different “life” from the one the family knew. The service may be uplifting, offering fascinating insights into the loved one’s other world, but afterwards?

Then the family finds itself playing host to a clutch of friends and an army of strangers, feeding and watering people they have never met before and will likely never see again. And these hordes are not even talking about the husband, father, grandfather. They’re talking about themselves, their projects, their past glories and future plans.

So I’m here to give thanks not only for Charlie, the most charismatic person I have ever met, but also to Rachel, Emma, Luke and Lily for welcoming us yesterday. I do hope the children were suitably rewarded once the suits and blazers came off.

Tributes

As to those thanks for – and to – Charlie, there were of course tributes at the service: from Phil Webster on how great a journalist he was and from Brough Scott on how poor a horse rider he was. The expletive-filled incidents have been well documented (don’t get me going again on “Where the **** is Chad” – though I was delighted to learn from Emma that a family geography game always includes that phrase), but there were more stories of individual kindnesses – both personal and professional – that will not have surprised in their nature, but may well have done in their number.

Those of us on the receiving end may not have realised how many others were similarly blessed – that we were not so special after all. Of course we weren’t. If nothing else, these occasions serve as a sobering reminder of how small a part (however vital on occasion) most of us play in the big enterprise.

Naturally, the go-to phrase for people paying tribute yesterday has been that Charlie was a great journalist – typified in Rupert Murdoch’s message, read out by his daughter, recalling him awakening the Chicago Sun-Times subs from their sleep to do a slip edition on the death of Soviet leader Yuri Andropov. Well yes, he was. But there have been many great journalists. Charlie’s uniqueness lay in his qualities as a leader, insightful and inspirational, knowing when to swear and when to guffaw, spotting and developing talent, encouraging people to hone particular skills. I used to complain that that meant people were put in “boxes” that restricted their ability to grow. I couldn’t have been more wrong. It was about building the best possible team with everyone playing their strongest game in their ideal position, rather than overpromoting people to their positions of incompetence.

Oh, the joys of hindsight.

Rupert Murdoch

That Murdoch tribute began with a description of what the proprietor regards as the requirements of a great journalist, which makes, shall we say, interesting reading:

“A passion for the truth, fox-like cunning in dealing with bloody-minded officialdom and the skill to seek out and write clearly the stories that readers want to read. Above all, great journalism requires courage. And Charlie Wilson was a great journalist.

“He had the courage as an editor of The Times to print stories that those in power, be they government ministers or gangsters, did not want to see. He had the courage to take a story further than Fleet Street rivals, risking heavy legal sanction. He had the courage to lead his staff through the bitter dispute at Wapping – and occasionally, very occasionally, he had the courage to admit he was wrong.”

Hmmm. This from the proprietor of the paper that recently removed a story that Boris and Carrie Johnson did not want to see.

The tribute goes on to say that some had questioned the appointment of a Glaswegian who had never been to public school or Oxford or Cambridge – or any university – as editor of The Times and claims that Wilson had answered such critics by increasing the circulation from 300,000 to 500,000.

Hmmm again. Circulation did increase under Charlie but, while there may have been a blip that saw it hit the magic half million, I don’t remember it reaching those heights regularly at that time. But then, as another renowned nonagenarian famously remarked, recollections vary.

Sales did indeed soar in the 1990s – upwards of 700,000 at one point. But that was under a different editor and came not from editorial excellence, but an aggressive price war aimed at putting the upstart Independent out of business.

By then, Murdoch had dispensed with the services of the “great journalist” who had delivered the move to Wapping. And replaced him with a man who had been both to independent school and to Oxford. To put it bluntly, the toffs were deserting the Times for the Independent and Murdoch wanted them back – both buying and producing the paper. The assumption was that those higher-class readers wanted their news from a higher-brow source, but when it came down to it, they just wanted it as cheaply as possible.

None of which reflects badly on Charlie, who was offered a non-job (as is Murdoch’s way when he has decided to replace his editors), but declined and went on to build an ever-more successful career elsewhere – including, for a time, at the Independent. He may have regarded becoming editor of The Times the pinnacle of his career, but surely the greater achievement was to sort out the pensions mess left by Robert Maxwell at the Mirror. Of course nobody would expect Murdoch to mention either the circumstances of the parting of their ways or his subsequent achievements.

Words to guide you

The final element of a service with fantastic music choices – Nobody Does It Better, When the Saints Go Marching In, the Post Horn Gallop – was what the rector called “the journalist’s prayer”. Whether or not you believe in a God to guide you, I would suggest that attempting to follow the path outlined in these words will serve you better as a journalist than fox-like cunning.

Almighty God,Strengthen and direct, we pray,

the will of those whose work is to write what many read,

and to speak where many listen.

May we be bold in confronting evil and injustice

and compassionate in our understanding of human weakness,

rejecting alike the half-truth that deceives and the slanted word that corrupts.

May the power that is ours, for good or ill,

Always be used with respect and integrity;

So that when all here has been written, said, and done

We may, unashamed, meet Thee face to face.

The state of The Fourth Estate

Finally, on a personal note (yes, I know this whole thing is personal), I was immensely flattered to be included in a book of anecdotes that Charlie’s daughter Emma had compiled for her children. She chose the opening few paragraphs from a blog post from a decade ago. Seeing them inspired me to go back and take a look at the whole thing. It’s about the dominance of Eton and Oxbridge and how the “fourth” estate is becoming as closed to ordinary people who have something to offer as the other three. I am proud to say that Charlie approved of it at the time. If only things had changed since then. If you are interested, you can read it here.

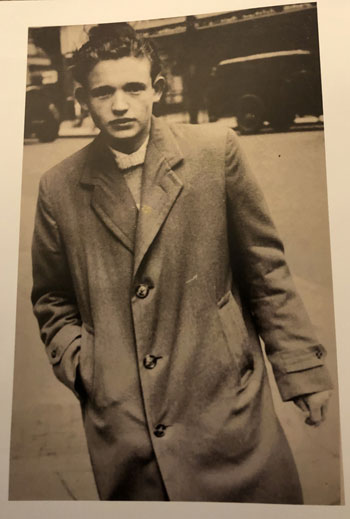

I am grateful to Emma for allowing us to reproduce this wonderful picture of the young Wilson and for the photograph of her with her mother, Annie Robinson, and Tom Stoppard.