With thousands dying around the globe and many thousands more suffering from the deleterious effects of coronavirus, it may seem as though press freedom is a relatively minor matter. Nothing could be further from the truth. The reason for the contagion’s rapid and uncontrolled spread is itself a manifestation of the lack of press freedom in the country where it began.

The Chinese Communist Party attempted to keep Covid-19 a secret and thereby denied the rest of the world the chance to prepare its defences weeks ahead of the news about the Wuhan outbreak finally breaking. In its bid to suppress the truth, the party’s police force arrested Li Wenliang, the doctor who warned his colleagues of the contagion, and infamously accused him of “spreading false rumours”.

Keep that malevolent, trumped-up, catch-all offence in mind because it has since proved to be the template for authoritarian governments across the world. Consider also the insidious effect of the president of the USA, who has turned reality on its head by labelling the truth as “fake news”.

Together, America’s Donald Trump, in the 'land of the free', and China’s Xi Jinping, in the land of the unfree, have become the world’s most powerful press freedom predators. They have provided a repressive blueprint for political leaders elsewhere, be they dictators, the nervous holders of office in fragile, developing democracies or even the ruling elites in settled democracies.

As a result, journalists seeking to tell the truth have been persecuted. They have been threatened, intimidated, arrested and beaten up. Newspapers have been banned. Websites have been blocked. Censorship has been granted a spurious legitimacy. By using Covid-19 as a cover, governments have instituted a range of actions which reveal their underlying hostility towards the exercise of press freedom. Lest you think I exaggerate, what follows is but a snapshot of dishonourable actions against journalists and their outlets.

At first glance, some incidents appear to be relatively minor clashes between individual reporters and members of the security forces. Together, however, they reveal an anti-press freedom paradigm which has seen journalists subject to high-handed treatment along with instances of almost casual brutality. These reinforce a disturbing trend of increasing antagonism towards those who work for mainstream media. In too many countries, the authorities now feel confident they can abuse journalists, even to the extent of denying them the right to life, because those who attack them enjoy the shield of impunity.

America’s Donald Trump and China’s Xi Jinping have provided a repressive blueprint for political leaders elsewhere.

The Sun sets in the East

Let’s begin with Russia – serial killer of journalists – and its former satellite states. When Covid-19 arrived, Vladimir Putin’s administration was quick to enact legislation which sought to prevent journalistic inquiries. A new law prohibits the spreading of supposed “false information” with punishments ranging from five-year prison terms to £20,000 fines. Media outlets found guilty of disseminating disinformation face fines up to £100,000.

On 15th April 2020, Russia’s media control agency, Roskomnadzor, ordered the Moscow newspaper Novaya Gazeta to delete an article by investigative journalist Elena Milashina because she criticised the lack of preparedness for coronavirus at hospitals in the autonomous republic of Chechnya. During a visit to the capital, Grozny, in February, Milashina was assaulted in a hotel lobby by a group of about 15 people. The attack, in which she suffered soft tissue injuries to her head, bruises and scratches to her shoulders and neck, was reported to the authorities but not investigated.

In Azerbaijan, freelancer Natig Izbatov was arrested by security forces for reporting on the challenges faced by people during the Covid-19 quarantine. Two journalists, Ibrahim Vazirov and Mirsahib Rahiloghlu, were detained for similar reporting and placed under “administrative arrest” for 25 and 20 days respectively. In Moldova, the health ministry refused to answer journalistic questions and arbitrarily lengthened the amount of time for formal responses to freedom of information requests from 30 to 90 days.

In Serbia, journalists were banned from attending daily Covid-19 press briefings by the health minister on the disputed grounds of the virus having entered “some newsrooms”. An online journalist, Ana Lalic, was detained overnight for “spreading panic” and damaging the reputation of a hospital by writing about its workers’ lack of personal protective equipment. Leaders of Serbia’s journalists’ union accused their government of “covert censorship”. There were reports of similar crackdowns in Romania and Moldova.

In too many countries, the authorities now feel confident they can abuse journalists.

The illiberal South

Many African countries with poor press freedom records added to their litany of authoritarianism and misconduct towards journalists. In Zimbabwe, freelance journalist Panashe Makufa was beaten up by the police and forced to delete video footage on his camera after filming a police operation to disperse people during the lockdown in the capital, Harare. His experience was mirrored in incidents recorded by international press freedom watchdogs in Nigeria, Ghana, Tanzania, Somalia, Zambia and Uganda, where a TV journalist was taken to hospital with serious injuries after being assaulted by police officers. In Sierra Leone, Fayia Amara Fayia, a reporter with the Standard Times, ended up in a wheelchair following an assault by a group of soldiers, who hit him with guns and kicked him, because he photographed a quarantine centre.

In India, the government sought to introduce censorship by urging the country’s Supreme Court to issue an order that media outlets should not report on Covid-19 without ascertaining “the factual position” from the government. The court rejected that request, but officials in various states tried other routes to suppress news about coronavirus. The chief minister of Maharashtra banned the distribution of newspapers on the fallacious grounds that it could spread the virus. In Tamil Nadu, the founder of a news website was arrested for publishing an item about problems faced by healthcare workers.

India was also one of the first countries to use the contagion as an excuse to restrict online access to its citizens. In company with Egypt, Iran and Ethiopia, it prevented the normal operation of the internet, effectively obstructing or denying news websites the capability to report on behalf of their audiences.

Three south-east Asian countries, under the guise of crisis measures linked to the pandemic, passed laws that give their rulers censorship powers. Vietnam’s autocratic regime can now fine social media users for publishing or sharing what it deems to be “fake news”. Cambodia’s emergency legislation allows its government to monitor communications, control media output, and prohibit the distribution of any information which could generate public fear or damage national security. In Indonesia, journalists face an 18-month sentence if they are found responsible for publishing not only incorrect information about Covid-19 but also “hostile information about the president and government”.

Many African countries with poor press freedom records added to their litany of authoritarianism and misconduct towards journalists.

Levantine liberalism. Not.

Governments in several Middle Eastern countries, where journalism is barely tolerated anyway, decided to tighten their grip still further. Iraq suspended the licence of the Reuters news agency for a story claiming the number of Covid-19 cases in the country was higher than officially reported. In Iraqi Kurdistan, four journalists were arrested for a range of stories critical of the autonomous government’s handling of the Covid-19 crisis. The United Arab Emirates introduced a series of fines should journalists publish medical information that contradicts official statements. In Jordan, security forces arrested the owner of Roya TV and its news director for airing a segment in which people from the poor districts of the capital, Amman, criticised the nature of the Covid-19 lockdown. They were sentenced to 14-day detentions.

Then there is Turkey, which had the dubious distinction for four years of being the world’s leading jailer of journalists, a title regained by China last year. It added to its prison population by arresting the veteran Turkish journalist Hakan Aygun for posting an item on social media that belittled the campaign by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to raise funds for Covid-19 victims. Days later, the country’s broadcasting regulator banned Fox TV from airing its prime time news show for three consecutive days because presenter Fatih Portakal had the temerity to criticise the state’s coronavirus policies.

Governments in several Middle Eastern countries, where journalism is barely tolerated anyway, decided to tighten their grip still further.

Back home in Europe

Within Europe, there is not much doubt about press freedom’s greatest menace. Step forward Viktor Orbán, prime minister of Hungary. In a country where he and his oligarch cronies control some 80% of the print and broadcasting outlets, he was not prepared to allow any criticism of his handling of the pandemic by independent media which, according to him, were guilty of publishing disinformation.

So, at the end of March, he oversaw the passing of a special “coronavirus” law which allowed him to rule by decree for an indefinite period. Anyone found guilty of publishing what his government holds to be “fake news” faces prison sentences of up to five years. A Reporters Without Borders spokesman referred to it as an “Orwellian law [which] introduces a full-blown information police state in the heart of Europe”. The law runs counter to the European Union’s ethos and contravenes the rights guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights.

But Orbán has admirers, notably in Poland where a similar form of “media capture” has occurred. Its main public broadcaster, TVP, is controlled by the ruling Law and Justice party and has been a slavish cheerleader for the government throughout the Covid-19 crisis while denigrating political opponents.

Coronavirus merely amplified the underlying dangers.

Isolated incidents?

The pattern could not be more obvious. Unprincipled governments without any regard for press freedom before the coronavirus outbreak have used it as a way of constraining press freedom still further. Nor should we overlook the fact that in democratic states in the European Union, where freedom of the press is often taken for granted, specific Covid-19 pandemic measures challenged journalists’ ability to work freely. According to a paper published in late April by the International Press Institute (IPI), its researchers found examples of excessive regulation, unnecessary restrictions on information and inappropriate surveillance of journalists. Some reporters and photographers also told of being verbally and physically attacked.

The year 2019, prior to the contagion, was anything but a good year for press freedom. Coronavirus merely amplified the underlying dangers. In the future, in a post-pandemic world, editors and journalists will surely need to battle to ensure that those supposedly temporary emergency powers do not become permanent barriers to their ability to inform the public.

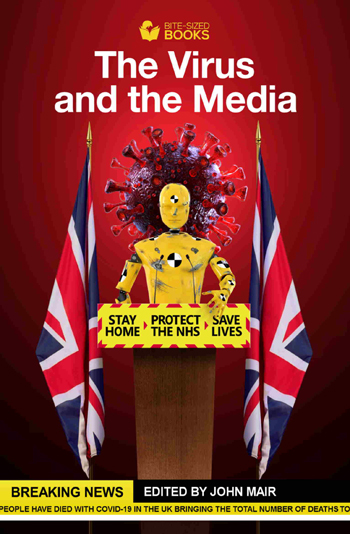

This article features in the new book, ‘The Virus and the Media: How Journalism Covered the Pandemic’ edited by John Mair, published by Bite-Sized Book. A version of this article was first published in An Phoblacht in May 2020.