20 September 2023

Dear reader,

Greetings from Male (or Malé or Male’, depending on your style book), capital of Maldives, an archipelago of atolls perched off the tip of Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean.

I’m staying in the centre of the city and it has a lot of similarities with other places I know well, like Port of Spain in Trinidad & Tobago and Kampala in Uganda: chaotic, busy, noisy, smelly, hot, wet, full of people, and traffic.

But one thing it doesn’t have is drink, or more specifically alcoholic drink – and I don’t miss it for a moment.

As an Islamic state, it is a dry country. Alcohol is not available to consume or buy. I’m told drinks can be had on the swanky resorts away from the capital. But at upwards of US$250 for a day pass, I think I’ll, er, pass.

There is no bar culture leading to drunks in the street, pools of vomit, fighting, bottle throwing, and the general unease that blights not just the cities but small towns across the UK.

I’m here as part of a team delivering a ‘Strengthening Communications Governance’ and have met courageous and industrious journalists as well as forward-thinking educators and media regulators.

Doing journalism in the Maldives

It’s not the easiest of places to do journalism. There are no printed newspapers – just think about the logistics of it – so written work is published online via ‘news’ websites that are particularly opaque about their origins, sponsors, and commercial activity. A state TV station, Public Service Maldives, does a good job of keeping on top of government activities, while other TV outlets provide a diet of news and entertainment.

In terms of daily life, the practice of religions other than Islam is prohibited by the constitution and the religious unity law. A Hindu priest who tried to hold spiritual healing classes in Malé was arrested and deported when the Islamic minister asked the police to take action after the spiritual healing classes were advertised on social media.

The wider issues of the environment, climate change, and global issues like land use and rubbish disposal are never very far away. Most of the 1,200 coral islands grouped in a chain of 26 atolls are too small to sustain any meaningful local life and are instead populated by the exclusive (that is, expensive) resorts the country is best known for.

Climate crisis on the horizon – does anybody know?

With an average ground level elevation of just 1.5 metres above sea level, and a highest natural point of only 2.4 metres, it is the world’s lowest-lying country. As a result, the Maldives are in danger of being submerged due to rising sea levels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations thinktank, has warned that, at current rates, sea-level rise would be high enough to make the Maldives uninhabitable by 2100.

Not that you’d know any of this by following local politics.

Reporter Shahudha Mohamed monitored the 9 September 2023 presidential election for popular online newsbrand Dhauru and wrote a comment piece that said: “With the presidential election less than a month away, not a single one of the eight candidates has paid attention to climate change.”

Another environment reporter, who did not wish to be named, said one of our biggest challenges regarding environmental issues is lack of proper data and research, but no candidate proposed a way to address that either. “I feel like candidates have largely ignored the concerns raised by the general public during the past years and have failed to give climate change the focus it must be given,” they said. “Even the pledges that have been made are extremely vague, such as ‘will carry out development projects in a sustainable manner’ and mostly focus on conservation. There has been almost no attention given to adaptation measures even though experts have warned us that the time for mitigation in Maldives has long passed and we must now be directing our valuable resources towards establishing adaptive measures.”

The insider’s view: grants and collaborations

For an expert view on all things environmental in the Maldives, I enlisted the help of Rae Munavvar, who has worked in many sectors of the media industry for nearly a decade, from building newsrooms and selling news to teaching journalism classes across the archipelago. Best known for launching ‘The Edition’ and her role as its first managing editor, she now works as a freelance journalist, writing for local and international outlets.

Noted for her outspokenness on matters concerning the rights of journalists, she is a passionate advocate for environment and conservation issues, and is the founder of Covering Environment, a non-profit initiative that focuses on improving eco-centric reporting across Small Island Developing States (SIDS) such as the Maldives.

Rae believes that the attitudes in the Maldives towards the environment are generally favourable. “Climate change is far too much of a reality for people to claim that weather patterns are unchanged and so forth,” she says.

“However, too many journalists, particularly at the editor level, don’t understand the intricacies of the climate crisis or our geographical vulnerabilities well enough to discern, or translate into general reporting, how multifaceted the problem is. They, therefore, may lack the ability or interest to adequately guide upcoming journalists, to whom the topic is of far more relevance, compared to the mentoring they receive in other areas.”

As a result, Rae finds that otherwise capable newsrooms are not always as prepared to integrate the environmental perspective into general reporting as they could be. “In this age, environmental concerns, particularly related to climate change, interconnect everything from housing to sports and fashion, especially in the context of vulnerable SIDS. I believe these concerns must be represented across beats internationally as well as on the local front,” she says.

Another issue that Rae believes they face in the Maldives is, many editors tend not to grant much airtime or space to these topics. “They tend to exhaust readers – however I believe that journalists can and should pursue different avenues to counter this challenge and present stories that inspire urgent action, but in a media market that’s as concentrated as ours, with a limited investor pool and battling poor economic forecasts, too often it feels like an impossible argument to win.

“Perhaps the situation could be improved through focused grants, and collaborations proposed by international news outlets – if the journalists can get more value out of it, they can advocate for their pieces, and higher-ups may be convinced to invest in the pursuit of the many, many important environmental stories that we must tell before it’s too late.”

Your environment correspondent writes

In search of my own environmental reporting, I head to Villingili, a traffic-free island a 10-minute and 15p ferry ride from the hustle and bustle of Malé. That I even make it is partly due to the alertness of the ticket office who advised that I did not really want to go to Thilafushi, my original destination, the artificial island created 30 years ago as a municipal landfill, or ‘rubbish island’ in journalistic shorthand.

“That is not somewhere you would want to go,” says the ticket clerk, which makes me want to go even more. But it becomes clear that a ticket will not be forthcoming so I settle for Villingili instead.

Just two kilometres from Malé, it feels a world away. There are two beaches, some shops, and a relaxed vibe, partly generated by the lack of traffic. There are plenty of boats tied up but also lots of unsightly rubbish bobbing in the blue water and some garbage on the beaches. But not as much as there could be, as I find out from Thanzy from Save the Beach, a volunteer group that has so far collected an amazing 31,416 tonnes of rubbish from the island’s beaches.

“We also deal with coral restoration and rehabilitation plus community outreach, engagement, research and education,” says Thanzy as she walks carefully along the beach picking up plastic bottles, cigarette cartons and food wrappers – the typical haul of rubbish collectors.

On the way back to Malé, I try to envisage what 31,416 tonnes of rubbish might look like and fail miserably as the rhythmic chug of the ferry and the soporific temperature sends send me quietly off to another place.

But it’s a lot of stuff that has been tossed aside without a care for either this world or any other world.

Lessons for Environment Reporters

A training programme called ‘Eco-friendly reporting’ run by Covering Environment with the Maldives Journalists Association gives a clue to the challenges faced by islanders writing about environmental issues.

Among the topics highlighted were:

What’s the hold up with environment reporting?

- Writers find it difficult to delve into the topics

- Lack of understanding leads to confusing narratives

- But probably most of all… readers seem hesitant to engage with such articles

Key issues noted by readers

- Outdated or off-putting language

- Improper use of data

- Too simple or overly technical

- Triggers anxiety and / or induces despair

Emerging issues

- Corporate imperialism takes over environment narratives

- The (yet-to-come-into-effect) plastic ban; how will it take place, are the people ready, alternatives available?

- Longline fisheries; intended to override existing Tuna fisheries’ marketing, tax challenge?

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) conundrum; can we really blame the watchdog when the ministry mandates are clearly in conflict?

- Disposal of rubbish, especially medical waste

Creating your environment piece

Do:

- Take everything you learn with a grain of salt!

- Make use of the knowledge you’ve gained to inspire discourse

- Shape exciting narratives that spur awareness among public

- Research problems that have not yet been brought to focus

- Look at environment issues from a Maldives-specific lens

Don’t:

- Go back to business as usual!

- Rely on faulty research or stick to only a few sources

- Churn out blame without considering the state’s role, and international factions

- Wholly follow data that favours developed nations or is skewed against indigenous communities and Small Island Developing States

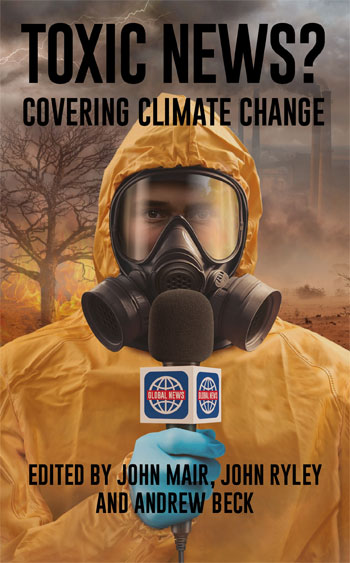

This chapter was taken from the new book, ‘Toxic News? Covering Climate Change’, edited by John Mair, John Ryley and Andrew Beck, published by Bite-Sized Books and available from Amazon in paperback, Kindle and eBook formats.