Legacy social media such as Facebook and X have been actively reducing the prominence and role of news on their platforms and investing more in content that they see as more fun and engaging for their uses. This includes content by creators and influencers, as well as formats such as video that are designed to keep people within the platforms rather than link out to publisher websites or apps. Taken together, these changes have led to the near collapse in mass referrals, meaning that publishers will have to work much, much harder to earn the public’s attention.

These private companies do not have any obligations to the news, but with so many people now getting much of their information via social and video platforms, changing platform strategies could have important consequences not only for the news industry, but also our societies. As if this were not enough, rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are about to set in motion a further series of changes including AI-driven search interfaces and chatbots that could further reduce traffic flows to news websites, adding further uncertainty to how information environments might look in a few years.

Social media shifts and the rise of video platforms

In many countries, we find a dramatic decline in the use of Facebook for news, and a growing reliance on a range of alternatives including messaging apps and video networks. Facebook news consumption (37%) is down four percentage points across all countries after a similar fall the previous year. By contrast, video-based networks are growing rapidly. YouTube is used for news by almost 31% of our global sample each week and TikTok (13%) has overtaken X (10%), formerly known as Twitter, for the first time.

Video is proving increasingly popular with younger internet users and across demographics in much of the global south. Short news videos are accessed by 66% of our global sample each week, with longer formats attracting around half (51%). Our research also finds that users of TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat tend to pay more attention to social media influencers and celebrities than they do to journalists or media companies when it comes to news topics. This is in contrast to legacy social networks such as Facebook and Twitter/X, where news organisations still attract most attention and lead conversations.

Traditional media struggle to compete with youth-based influencers in newer networks

The report documents the rise of a new generation of news creators such as France’s Hugo Décrypte, who produces explainer videos on TikTok and YouTube and was cited by survey respondents more often than legacy publishers Le Monde or Le Figaro. Jack Kelly’s TLDR brand in the UK and Vitus Spehar’s ‘Under the Desk’ TikTok account in the US are also popular with younger consumers.

Other well-cited creators include outspoken politics hosts such as Tucker Carlson in the United States and Piers Morgan in the UK, who have both embraced online streaming after leaving traditional TV outlets.

Meanwhile successful political podcasters such as Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart (the Rest is Politics) have embraced video distribution in the last year.

Consumers are adopting video because it is easy to use, and provides a wide range of relevant and engaging content. But many traditional newsrooms are still rooted in a text-based culture and are struggling to adapt their storytelling while the business side is also reluctant. The main focus of news video consumption is via online platforms (72%) rather than publisher websites (22%), increasing the challenges around monetisation especially for subscription-based news media.

Concerns about the extent of unreliable content are widespread

In a year that has seen a record number of elections around the globe, concern about misinformation has risen further with worries about AI-generated content a contributory factor. Concern about what is real and what is fake on the internet when it comes to online news has risen by three percentage points in the last year with around six in ten (59%) saying they are concerned — even higher in a number of countries holding elections this year including South Africa (81%), the United States (72%), and the UK (70%).

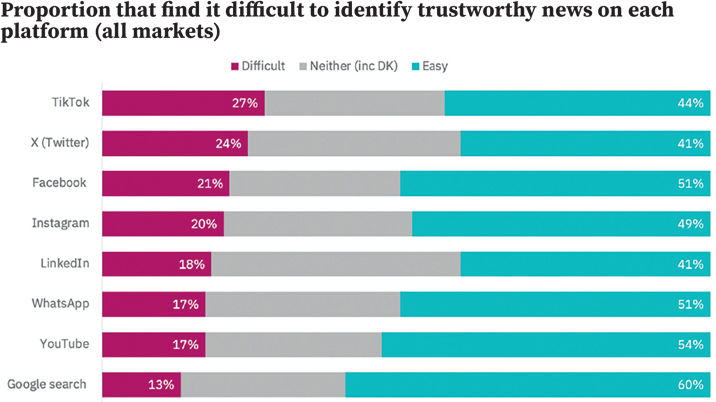

Worries about how to distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy content in online platforms are highest for TikTok and X when compared with other networks. Both platforms have hosted misinformation or conspiracies around stories such as the war in Gaza, and the Princess of Wales’s health. Qualitative research in the UK, US, and Mexico suggests growing concern about AI generated ‘photo-realistic’ pictures and so-called deepfake videos.

“I have seen many examples before, and they can sometimes be very good. Thankfully, they are still pretty easy to detect but within five years they will be indistinguishable,” was the response of a 20 year old male respondent from the UK.

AI and the news industry

In the last year, we have seen media companies deploying a range of AI solutions, with varying degrees of human oversight. Nordic publishers, including Schibsted, now include AI-generated ‘bullet points’ at the top of many of their titles’ stories to increase engagement. One German publisher uses an AI robot named Klara Indernach to write more than 5% of its published stories, while others have deployed tools such as Midjourney or OpenAI’s Dall-E for automating graphic illustrations. Across the world, we also find an increasing number of experimental chatbots and avatars presenting the news. Nat is one of three AI-generated news readers from Mexico’s Radio Fórmula, used to deliver breaking news and analysis through its website and across social media channels.

Elsewhere, we find content farms using AI to rewrite news, often without permission and with no human checks in the loop. Industry concerns about copyright and about potential mistakes (some of which could be caused by so-called hallucinations) are well documented, but we know less about how audiences feel about these issues and the implications for trust overall.

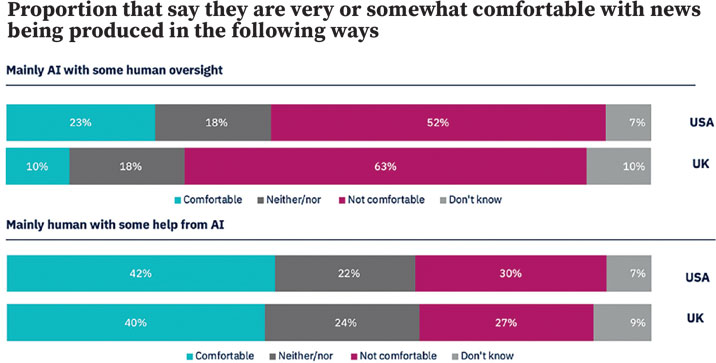

In our survey this year, we find widespread public suspicion about how AI might be used in creating content, especially for ‘hard’ news stories such as politics or war. There is more comfort with the use of AI in behind-the-scenes tasks such as transcribing interviews or summarising materials for research; in supporting rather than replacing journalists.

Respondents in the United States are significantly more comfortable about different uses of AI than those living in the UK, perhaps reflecting different attitudes to regulation of mainly US-based tech companies.

Business pressures mount

Advances in AI bring opportunities for efficiencies in the news industry but also further questions about where growth will come from especially if search traffic becomes affected by AI driven interfaces. Traffic to websites remains sluggish and digital news subscription growth has also slowed. Just 8% say they have paid for any online news in the UK, one of the lowest in our survey and we also find that almost half of these are paying less than the full price. Northern European countries such as Norway (40%) and Sweden (31%) have the highest proportion of those paying, along with the United States (22%).

Prospects of attracting new subscribers remain limited by a continued reluctance to pay for news, linked to low interest and an abundance of free sources. The vast majority (69%) of those that are not currently subscribing in the UK say that they would pay nothing for online news, with most of the rest prepared to offer the equivalent of just a few pounds per month. Elections have increased interest in the news in a few countries, including the United States (52%, +3 points from last year), but the overall trend remains downward. In the United Kingdom (38%), interest in news has almost halved since 2015. At the same time, we find an increasing number of people (46% in the UK) saying they sometimes or often avoid the news. Open comments suggest that that this relates to the depressing nature of news these days including intractable conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East. But disillusion with politics and the way it is covered is part of the mix too. In exploring user needs around news, our data suggest that publishers may be focusing too much on updating people on a few big stories and not enough providing different perspectives on issues or reporting stories that can provide a basis for occasional optimism.

Our report this year sees news publishers caught in the midst of another set of far-reaching technological and behavioural changes, adding to the pressures on sustainable journalism. Traffic from social media and search is likely to become more unpredictable over time.

Interest in the news has been falling, avoidance is on the rise, trust remains low, and many consumers are feeling increasingly overwhelmed and confused. Artificial intelligence may make this situation worse, by creating a flood of low-quality content and synthetic media of dubious provenance.

But these shifts also offer a measure of hope that some publishers can establish a stronger position. In a world of superabundant content, success is also likely to be rooted in standing out from the crowd, to be a destination for something that the algorithm and the AI can’t provide while remaining discoverable via many different platforms. Do all that and there is at least a possibility that more people, including some younger ones, will increasingly value and trust news brands once again.

The Digital News Report 2024 report is available here.

This article was first published in InPublishing magazine. If you would like to be added to the free mailing list to receive the magazine, please register here.