Peter Jukes is probably best known now as co-founder and executive editor of Byline Times, the website and newspaper that seeks to cover the stories underplayed or ignored by the established media.

Yet it all started off in a very different, and apparently illustrious direction in his twenties – a state schoolboy with a double first in English from Cambridge who had his early plays performed by young aspiring actresses such as Tilda Swinton and Johanna Scanlon.

Contemporaries at the Cambridge Footlights included Emma Thompson, Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry.

There was even a student director’s drama award and a book for Faber & Faber, A Shout In the Street, about London, Paris and Leningrad, as it then was, about modernity, urbanisation and art.

“It was a montage of images and quotations,” says Jukes who explains that he loved writing for other people, doing other people’s voices and getting into other people’s heads.

There was a hint, perhaps, of what was to come when friends suggested that he might be better as a tabloid journalist where he could find his own voice.

But he still ploughed on. He wrote the book for a fringe production, Matador, because he loved flamenco dancing, though the dancing was considered better than the drama.

There was a spell as a BBC radio producer and then Jukes devised and wrote Bad Faith, a Radio 4 series starring Lenny Henry as a police chaplain who had lost his faith. Mainstream television writing was to follow.

Given so many achievements across such a broad media canvas, it seems almost rude to ask, why so many?

“Why? Because I was a lost soul. I always used to say I was jack of all trades and master of none,” Jukes replies although the self-judgement seems harsh.

With Jukes, many things are lived in the reverse order, or at least, the reverse of the way most people progress.

There are many examples of journalists using their career in print or television to move on to write novels or plays or choose the law or public relations.

Later starter (to journalism)

Peter Jukes finally stumbled into journalism as he approached 50, an age when many are being shown the journalistic exit. The gradual transformation happened after Jukes had been warned that his career “was all over the place”.

The first step was influenced by suggestions that a decline in the number of public intellectuals was being matched by a rise in importance of investigative journalists.

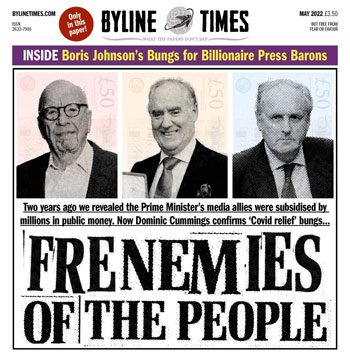

It was very difficult to debate ideas, Jukes thought, if we did not know the basic truths of our society. The thought led to a book on Rupert Murdoch: The Fall of the House of Murdoch.

In it, Jukes identified what he thought were multiple contradictions in the make-up of the media tycoon: he hates the monarchy but is himself a dynast; a largely self-made man who wants his children to inherit and a free marketeer who loves a monopoly if he can get one.

Jukes believes that the Murdoch empire “took a darker turn” when it got rid of the Fox television business and he sees the media tycoon as “a malign influence”.

When the News International phone-hacking trial came up, Jukes thought he had better go along to get some material to update the book and managed to get a last minute ticket.

Much to his surprise, the presiding Judge, Mr Justice Saunders, allowed live tweeting from the court.

“Nobody knew he was going to do this. I had my iPad and I started live tweeting and suddenly I got all these followers,” says Jukes who was soon being followed by more than 12,000 people interested in the trial of News International executive Rebekah Brooks who was ultimately cleared.

Jukes, who was short of money at the time and had missed a mortgage payment for the first time in his life, wondered whether he could use crowd funding to raise £4,000 to cover his mortgage and pay for staying at the Old Bailey for three months.

The money was raised and more, and eventually Jukes got £40,000 to cover the eight month trial and the book based on it.

It was riveting and very interactive. People would ask questions about the trial and Jukes would always answer.

“It was very dramatic – much more dramatic than writing about a (fictional) car chase or murder,” Jukes says.

One of his conclusions following the phone-hacking scandal is that greater regulation of the press is necessary and he is critical of the general libertarian press view that any move towards regulation is state control.

“Traffic lights are not state control. We need regulation particularly in a complex society. It is simplistic to say that any intervention by any collective body, a council, a government, the law courts is state control,” Jukes argues.

Crowd-funded journalism

His long path to journalism took another turn when Jukes was approached by a South Korean entrepreneur, Seung-yoon Lee, and Economist journalist Daniel Tudor who were launching a crowd-funded journalism site, Byline.com. There were several such sites in the US and it was seen as the next new thing.

After a year, the main lesson learned was that it was very difficult to scale up journalism sites and the operation was left to Jukes to take on.

Stephen Colgrave, an old friend who had spent most of his career in advertising, said he must do it but go offline through a festival of journalism.

Three festivals were run and attracted thousands of people and featured appearances from everyone from John Cleese and Anne Cadwallader to the Russian protest band Pussy Riot.

It was all great fun with streams on journalism and world affairs, word from the latest investigations and dancing into the night.

Slowly, Jukes realised that the bigger the festivals got, the more money they lost.

In the latest example of Jukes “doing my life in reverse,” a core of top journalistic contacts had been assembled by the festivals and a monthly newspaper and website grew out of the events.

There was even a crazy thought of trying to buy The Independent. This was abandoned when Saudi investors took a stake, setting a value that was way out of their reach.

Partly influenced by the retro trend back towards vinyl in the music market, they decided to mark the launch of the website with a print edition which they found surprisingly cheap to produce. If you can produce a copy for around £1 and sell for £3…

Subs-based

They decided to avoid the retail route on grounds of cost and go instead for subscriptions and what is effectively print on demand, although you have to move up in increments of 1,000 copies.

Byline Times launched in March 2019 with a Brexit special devoted to the idea that Brexit hadn’t just exposed the weakness of our political system, but also the lack of effective journalism to hold it to account.

“The best example of this is the glaring lack of action over, or even acknowledgement by the government and most of the press, of the democratic interference in the EU referendum through social media, illegal spending and foreign influence.”

They would all become preoccupations of Byline Times which would largely ignore the daily news cycle and concentrate instead on “what the papers don’t say”.

After two weeks, they had 500 subscribers, which meant that out of the initial minimum press run of 1,000, there were 500 copies hanging about the office to be given away free.

Around £300,000 had been raised from private investors and crowd-funding for the website, newspaper and later, Byline TV, and breakeven was reached by the end of the first year.

Now, subscriptions have risen to 24,000 bringing in around £60,000 a month with a further £70,000 from subscribers who pay extra to keep free access to the website. The hundreds of names of these super subscribers are carried on the front and back of each month’s issue.

The paper, with regular columnists such as political journalist Peter Oborne, has honed in on everything from the activities of Cambridge Analytica, and the links between multi-million PPE contracts and Tory donors, to, more recently the origins of Trussonomics in the right-wing think tanks of Tufton Street.

Jukes says he is heartened by the fact that the mainstream media are now all over many such stories, highlighted long before on Byline Times.

“The challenge is, where do we now go next? We like those kind of problems,” says Jukes who adds that the greatest kudos he gets is from the readers.

“People know when we do an investigation, it’s in the public interest and a matter that needs to be exposed,” the Byline Times executive editor explains.

Most of the themes of the monthly newspaper emerge from the website and then there is the usual scramble with the front page often changing the day before publication mid-month.

“It’s tough being a magazine for rhythm but with a newspaper agenda,” says Jukes.

The modest but effective financing model is producing enough funds for expansion with the launch of a digital online supplement aimed at younger readers and a cultural section for the newspaper on the cards.

Does Jukes see Byline Times as his greatest achievement?

“I love the idea that there is a masthead there that I am deeply proud of but it’s a collective achievement, a group achievement and that is something that pleases me beyond my bones that there is something that will survive me and a younger generation takes over,” says the man who finally became a journalist in middle age.

Peter Jukes has not, however, given up his old life entirely. He is at work on a play with director Stephen Unwin called The Russian Ambassador. Answers on a postcard to InPublishing on the identity of the ambassador.

This article was first published in InPublishing magazine. If you would like to be added to the free mailing list to receive the magazine, please register here.