This media year, as it winds towards its end, seems pivotal, a hinge year – the year that everything cracked apart. For over a decade, we’ve been waiting for the tectonic plates of print survival to shift. Through 2017, that slide has definitively quickened as more and more local papers have closed or decided to print only once a week. The Wall Street Journal has axed its European and Asian print editions. Soon British casualties alone will be hitting 400 titles - and the merger of Trinity Mirror and Richard Desmond’s stable at national level signals more upheaval. The future we’ve long agonised over is now.

The problem, though, is that this future has always been vague and elusive, a constantly shifting array of possibilities, trends, dreams and blind alleys. And so it still seems today. All media life is a journey. But to what destination?

The iPhone effect

Take print. It’s been an easy assumption for almost two decades now that words on paper would soon be a thing of the past. Words on laptops and then tablets – as with Rupert Murdoch’s tablet-only The Daily – would inevitably take over. But then came the explosion of smartphones, fuelled by the first iPhone only ten short years ago.

So mobile phones became the prime medium of choice. They are the present, fuelling growth in news via social media. They also appear to be tomorrow’s dominant form of communication. Some 91% of 16 to 75 year-olds, surveyed for the annual Deloitte report, had switched on their smartphones in the last 24 hours: 47% of 16 and 17 year-olds were using them to stream films and TV programmes (compared with only 2% of 65-75 year-olds). Your mobile phone, in short, isn’t some optional appendage to modern life. In ten years, it has become integral: the personal computer that guides you through life.

Where, pray, does that leave old friends dropping in? (as Manchester Evening News ads used to claim). Peripheralised as a source of rolling news. Revenue squeezed as Google mops up the small ads they used to rely on. Out-gunned as Facebook gathers display. Deserted as the tide of media change sweeps on.

And yet, awkwardly, that is not quite the end of the story. Print may be enduring a tough and threatening time. But look at magazine circulations and some winners stand out - Private Eye, Prospect, The Economist, The Spectator and the New Statesman, The Week. These, for the moment, are still basically print-based publications. Indeed, the Eye makes only a fleeting attempt to exist online. But, once a week at least, they still find a ready audience. A traditional mixture of news, analysis and opinion flourishes on printed pages.

“I don’t happen to believe that print will disappear anytime soon, at least among established and trusted brands like the FT, New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Washington Post”, the editor of the Financial Times, Lionel Barber, declared recently. He’d probably find Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail agreeing with him, one small sliver of solidarity.

But never forget that, in the onrush of media change, there are many ephemeral steers and diversions. Go back three years, for instance, and the twin giants, Google and Facebook, were hailed as potential saviours of publishing, offering special treatment and revenue streams to beleaguered newsmen. Bitter experience turned that on its head. Continuing experience will keep on changing perspectives.

2017 hasn’t been a good year for the forces of Silicon Valley. They seemed so vast, so mighty, that nothing could stand in their way. But events can swiftly put them on their back foot. Events like the anti-trust investigations and fines beginning to roll out from Europe. Events like the increasing hostility between Washington’s politicians and the Valley boys. Events like fake news.

The Fake News effect

Is revulsion against made-up news on confected websites anywhere in the globe (including Russia) overdone? Perhaps, a little. The fakers seemed to give Britain’s 2017 general election a wide berth. But there is a general taint to register here.

As Lionel Barber trenchantly puts it: “I believe the rise of fake news reflects a general decline in the terms of political debate and a related erosion of public confidence in our institutions.

“Right now, the environment is uniquely conducive to fake news because: We live in a world where there are no accepted facts, a world where facts are secondary to opinion and a world where the media landscape has fragmented. A world which has become intensely polarised.”

Fake news isn’t some isolated phenomenon then. It is a product of the frenzied, sometimes visceral world we live in. And if you ask any pollster which medium carries the highest quotient of fakery, the answer’s clear. Fakery blossoms on the internet. Fakery haunts your mobile phone. Trust is digital bust.

Thus the rising clamour, these past few months, for governments to see Facebook and the rest for what they are. Not mere innocent platforms, bringing you good or lousy information without discrimination or judgement, but as publishers, responsible for the facts – and falsehoods – they plant on your phone or office desks.

Let’s be honest. This has long seemed a convenient cry from conventional publishers, an attempt to cut the giants down to more regulated, less freebooting size. But throughout 2017, it’s been attracting the added traction of truth and relevance. Donald Trump and his relentless anti-media campaign has fanned the flames, constantly underlying what he sees as the lies the media tells. And the continuing investigations into his campaign teams’ links with Russia, and Russian merchants of fakery, underlines the gravity of the situation we face.

Simply, it comes to appear that something must be done. The internet's monsters must be brought within the ambit of normal press and broadcasting regulation. Proper news, brought to you by proper reporters, is a valuable commodity again.

Funding proper news

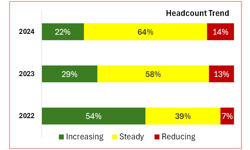

Which raises, for me, one of the great 2017 questions posed to the media itself. If news, trusted news, is at a premium, how can trusty newsrooms provide it in an era of closing papers and shrinking staffs? That death toll of titles I began with, and the savage staffing cutbacks that typify it, are the very antithesis of what seems necessary. But how can you argue with red-ink facts in the balance sheet?

There are increasingly useful ways of raising the cash that excellence demands. Foundations, in America especially, are stepping up to the mark. In Britain, the BBC, its arm twisted by government, is recruiting 150 journalists to work for and with local papers on the staples of news provision. Some paywalls – on the Times and arguably on the Daily Telegraph – are producing results. The Guardian’s membership scheme has made useful strides. But what there isn’t, yet, is a wider commitment to the survival of quality news collected by quality newsrooms. We’re still in a shrinking state.

Of course, bills have to be paid. Of course, shareholders need a return. But there’s also a trap in the forests of print decline. Run your newsroom down too far and, whether online or in print, you have nothing left. Our national press, just like our local press, has too many residual titles that have become almost empty shells. There is no real transition to digital existence because there’s nothing worth making the journey for.

Success in 2017, by contrast, tells a quite different story. Look to America. The Washington Post is a tremendous success, breaking the one-million subscription barrier this autumn. The Post has expanded staff, range and reach, not shrunk them. Its digital owner, Jeff Bezos of Amazon, is growing audience and importance by pumping in money. That's his recipe for digital hegemony applied to news. And, though the New York Times may not have quite those resources, it’s still holding the investment line, with 2.3 million digital subscribers.

It’s great when your punters pay for print copies and online as well. But make no mistake: growth in 2018 and beyond will have to be digital. And growth means investment of the kind the Daily Mail group has made in making MailOnline a clicking, chinking wonder of the online world.

What sort of investments work in this new world of opportunity? There’s the rub. No general rule provides revenue areas for all. No instant fashion – say the rush into video – is guaranteed money in the bank. I laughed over one InPublishing headline on its “View from the States” in its last edition. “Amid new revenue push, video is the solution du jour”.

Perhaps. Yet here, filed a few days later, is an analysis from the Columbia Journalism Review. “A pivot to video is really a pivot to declining page views … The numbers are chilling: According to data from comScore, the publishers that pivoted to video this summer have seen at least a 60 per cent drop in their traffic in August compared to the same period from a year ago.” Whoops? The menu of survival changes daily. You need to choose à la carte.

And here’s the way 2017 points to our future: full of hope as well as despair, full of fresh thinking and initiatives as well as stale gloom, full of change – with only a single common theme. There’ll always be news and a public’s thirst to discover what’s going on. If anything, that thirst is more dominant than ever, driven by the entire, expanding apparatus of communication, a force that in so many ways makes us part of one world of information. The future belongs to the newsrooms, professional, fully-staffed, innovative, that can meet that challenge. Many dishes on the menu, many possibilities. But only one central demand.