The existence of the economic cycle is widely debated. I believe in it, but a close friend, a world class economist, and mathematician, tells me I’m talking rubbish.

But looking back over OECD data over the last 40 years, and personal experience, my hunch is that not only is there a cycle, but that this recent downturn wasn’t it. The question therefore is: Is there more to follow? Ratings agency Moody’s thinks so. They recently headlined: "Revenues Set to Stabilize in 2010-11, But Long-Term Outlook Is Still Negative."

The OECD review reveals a number of things:

• Over the last forty years, what were then largely independently fluctuating economies are now aligning. Who would have believed two years ago that the existence of the Euro could be affected by Greece? Among major economies, in 1975, the fluctuation in GDP - ranging from -1% in Switzerland to +27% in the UK - was 28 points. By 1995 the difference between Japan at +2% and the USA at +5% was only 3 points. In 2009, the difference between the best and the worst – all negative - was 1.5%. Even Australia, which has outperformed other major economies during the recent crisis, still saw a significant reduction in economic growth.

• Despite my expert friend’s assertion, there appears to be a ten/eleven year cycle. The USA economy dipped in 1971/2, 1981/2, 1991/2 and 2001/2.

• Other factors have come into play: The oil crisis in the mid ’70s; 9/11 certainly didn’t help but the stats show, the economy was already slowing; Japan had a crisis in 1998 (caused by its liquidity trap – a code for bad banking practice) and is still continuing; Germany’s crisis was in 1987, (blamed on global competition). The UK generally lags the USA by a year, but it didn’t stop them faltering in 2005, (due to plummeting export demand – since Thatcherism put an end to UK manufacturing it is hardly surprising).

In each case we see a common cyclical effect in years 1 or 2 of the decade, and a man-made effect in between in different points. The problems are that firstly world markets are aligning, and secondly external influences - of which the banking fiasco is the most recent example - are becoming more universal.

But this can only lead me to conclude that Moody’s are right, and we are heading for a second, if not so serious, downturn. The so-called “double-dip”. And it is becoming increasingly global.

The news publishing industry is inherently highly cyclical. Our problem isn’t this per se, but the fact that in the past we have failed to learn from past experience how to manage it, and grow from it. So faced with this potential scenario, we need as the Chinese proverb says, “Plan for War, and Hope for Peace.” And the feedback is good.

One thing that the last two years has shown us is that newspaper companies can be remarkably, if painfully, resilient. Q1 profits this year for many companies were commendable. In the USA, many publishers, have dragged themselves back from bankruptcy. In France, with a highly complex labour market, the unions at Le Monde have recognised that they need new owners and investors, and in return they must give up some of their traditional control of the company, and are working closely with management at finding a new business model, and new investors.

But we need to keep going, and assume that firstly the decoupling between advertising revenues and GDP will continue, and that GDP itself may fall again in a couple of years time creating a second geometric impact on profitability.

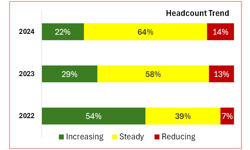

The hard challenge here this time is to get the costs out in advance of the coming economic deterioration, and not after the event. This is a painful and unpopular thing to say after so much sacrifice has been made across the industry, but better to slowly anticipate a need for further flexibility and belt-tightening, as Trinity Mirror are doing in the UK, than to suffer another heart wrenching period in a couple of years’ time. As the Economist reported earlier this month: “Newspapers have escaped cataclysm by becoming leaner and more focused”. But the fact is that newspaper companies were slow to anticipate what was coming, and even slower to react.

Hindsight strategy is not a great way to move forward. It’s easy for me to say this.

However next time around, I’m not talking about the USA, Germany or Japan. Because of economic and technological alignment, the next crisis could affect burgeoning markets, such as Australia, India, China and Thailand. To be blunt, the reality is that publishers should have had better tools in place to forecast the upcoming downturns, and better accounting mechanisms to respond to their consequences. Recruitment revenue cycles lead the economic cycle. Not the other way around. These indicators need to be implemented to ensure future profits are retained and enhanced. These are relatively easy tools to apply.

Of course there is much debate about the extent to which resource cut-backs have affected the quality, and long term performance of the industry. In the UK, a study by Ofcom, the media regulator, shows that readers’ perceptions of the quality of their newspapers have not fallen despite massive cuts in costs. Why? Because most of the savings have been made in production areas, which have been long-overdue (I first wrote about this in 2003). With some notable exceptions, there is still too much fat in non-creative or sales areas. Sadly as I’ve written before too, many cuts are still being made in revenue generating areas, with little investment in training and R&D.

So, having been so critical of my friends in the industry, what would I do in your shoes?

• Firstly I would buy fewer shoes! Establish a plan to remove an incremental 1% to 2% from my core fixed operating costs per year, regardless of revenue improvements, reserving the savings, not for greedy, disinterested shareholders, but to protect and grow the business. For a typical newspaper, with a 15% operating margin, an incremental 1% advance saving in costs per year would over five years generate 4.2% of turnover that could be devoted to New Product Development. This compares with Nestle who invest 2% of turnover on R&D and Google who invest 12%.

• I would establish a business development process – there are a range of options – not obsessed with digital, but in providing realistic solutions for media consumers and communicators. My experience is that simple, cheap research – talking to customers - reveals a string of opportunities.

• Finally I would agree with shareholders a long-term financial planning model for anticipating inevitable revenue cycles, so that the business can reinvest in development when things are good, and not be reliant on, or threatened by debt, when things get tough. This isn’t new thinking. The trends have been around for 40 years. The lessons to learn have been there for at least 20 years.

Follow my thinking. If I’m wrong about the double-dip, you’ll come out flourishing. If I’m right, well at least you’ll survive.