Remembering John Pilger

Suppose you were writing an obituary of Winston Churchill. How far in would you get before you mentioned the drinking, the boorishness, the racism? Would they be your intro? Would you mention them at all?

Intro? Don’t be daft. There’s all that war leader stuff to write about. Ignore them? Not that either. Unlike when the great man died, we live in an era of warts-and-all obituaries – although if you were a fan, you might play down those aspects of his character, maybe cover them in an amusing or telling anecdote.

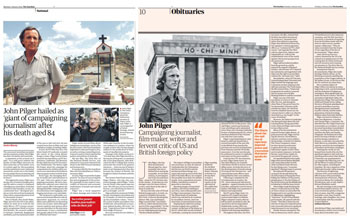

I ask because a giant of our trade died last week, a man portrayed by some as a flawed hero, by others as a villain with redeeming features and by one – the paper he worked for in his prime – as an absolute saint. Whatever else he was, John Pilger was certainly not the latter.

To me, as a student and trainee in the early 70s, Pilger was the ultimate reporter. Handsome, intrepid, forthright, he was the Hollywood archetype made flesh; exactly the sort of person to attract young idealists (I don’t pretend to have been such a creature) to the business. Note, I say reporter. I shall forever think of Pilger not as a “journalist” or a “foreign / war correspondent”, but as a reporter. He told stories and things changed because of him.

Between 1966 and 1979, he was honoured half a dozen times at the British Press Awards – twice as journalist of the year and once each as descriptive writer of the year, campaigning journalist, news reporter and international reporter. More honours would follow as he moved to television and documentary making. He told the world about the horrors of Pol Pot and the Cambodian killing fields, about the oppression of people in East Timor and the mistreatment of Aborigines in Australia. He was within feet of Bobby Kennedy when he was assassinated. Quite the role model.

And quite a lot to give an obituarist a reasonable intro, you’d have thought. Maybe just one of those achievements might provide what you need? Well, for the Times, the most compelling snapshot was Pilger being hoaxed as he tried to prove the existence of the child slave trade in Thailand. For the Telegraph, it was the fact that he had inspired the neologism “to pilger” – “to conduct journalism in a manner supposedly characteristic of John Pilger”.

A compliment at least? Hardly. The second paragraph attributed the verb to Pilger’s contemporary (they were born a month apart) Auberon Waugh, whose own explanation was, “it means when anybody who wants to make a good argument shouts and waves his arms about a lot and, oh, vaguely blames you for murdering Vietnamese babies”. And then, for good measure, it gives readers A A Gill’s take: “A particularly monotonous, self-righteous, partial and ism-bound view of the world, posing as journalism.” (Of course, no national daily could possibly be accused of serving up such fare. Immigration, wokeness, gender wars anyone?)

The Telegraph obit does then concede that Pilger was regarded by many as the finest crusading journalist of his generation and acknowledges some of his best work before returning to the way his world view – which obviously did not chime with that of the Telegraph – coloured his work and how he blamed the West and the mainstream media for many of the world’s problems.

Over at the Times, which gave Pilger second billing to the actor Tom Wilkinson, the story of the hoax slave girl leads into Waugh and his neologism, which is here given a different and more damning definition: “To present information in a sensationalist manner to reach a foregone conclusion; using emotive language to make a false political point; treating a subject emotionally with generous disregard for inconvenient detail; or making a pompous judgment on wrong premises.” (See note above, of course no national daily etc etc.)

There is a quick mention of his “Year Zero” Cambodia report having inspired almost $50m of donations towards rebuilding the country, with schoolchildren giving up their pocket money and “manual labourers handing over their entire weekly pay packets” (just how patronising can you get?), but then we’re back to what critics had to say about him and the way an “extreme left-wing and anti-American bias consistently underscored much of his reporting”. The winning of “numerous awards” and the impact of his work are almost an aside to the fact that there was “never once a single example of Pilger praising a pro-western leader or government”. Animus drips through the entire piece.

Meanwhile, the Guardian, for whom Pilger wrote a column until 2019, took two bites of the cherry, first with a “tributes paid” news story on Monday and then a full obit on Tuesday. The former was headlined “John Pilger hailed a giant of campaigning journalism…” and contained a comprehensive list of his greatest hits and fond memories from all sorts of people, from ITV’s Ken Lygo to Julian Assange’s wife and Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters. Not a dissenting word to be seen. The next day’s obit was equally starstruck, with no mention of slave girls or neologisms. A successful libel action over one of his Cambodia documentaries (which won an Emmy) and brushes with TV chiefs over impartiality are skated over, leading to the conclusion: “The ferocity of rightwing criticism of his views indicated the effectiveness of his journalism.” In other words, they hated him, so that proves he was right.

The Guardian gave a fairer rundown of his achievements, but on balance, I found the warts-and-all efforts from its ideological opponents, particularly the Telegraph, more palatable than its whitewash. They were both overwhelmingly negative in tenor, and may have overegged the significance of his pronouncements on Chavez, Putin, Obama, Blair and others. But these were part of who and what he was and shouldn’t be ignored. Put your own gloss on it by all means – as you’d imagine, Pilger’s support for Assange is a plus for the Guardian, a minus for the Times and Telegraph – but for heaven’s sake don’t pretend stuff didn’t happen.

If you read all three, you just about get a decent picture of Pilger’s work, but not one comes close to telling us much about him as a human being, beyond a barbed “Bollinger Bolshevik” sobriquet in the Times, coupled with a querulous anecdote about him stealing logs from a neighbour in Tuscany.

I raise a hat to the Express for having the grace to acknowledge his importance in a short leader that ended: “We might not always have agreed with Mr Pilger on every issue - but we admired his determination and unrelenting desire to expose the wickedness of the world.”

All three heavyweights would have done better to use that as a starting point.

… and when Auberon Waugh died…

The Telegraph made much of what Auberon Waugh thought about Pilger – both in the obit, which has him describing Pilger as “just another conceited hack like the rest of us”, and in a diary note by Michael Deacon in which Pilger is accused of almost killing Waugh. He apparently laughed so much at a pompous Pilger documentary that he ended up in hospital.

Waugh wrote for the Telegraph for years, and the paper is naturally more sympathetic to him, so I was intrigued to see how it approached its own man’s death more than 20 years ago. Here we have it: “Auberon Waugh, who has died aged 61, was the most controversial, the most abusive, perhaps the most brilliant journalist of his age - an acerbic wit, a traveller, a farceur, an epicure; above all, a hater of humbug in all its forms and of politicians in most of theirs.” It is impressive to see that “abusive” right up top. But the most brilliant? Hmm.

Henry Kissinger

I also thought it would be an interesting exercise to look back on how the three heavyweights’ obituarists treated Henry Kissinger when he died at the end of November. All “Nobel peace prize” and the greatest diplomat of the 20th century? Not entirely. All three were more even-handed than they were with Pilger, with the generally admiring Times and Telegraph using words like “manipulative” and “furtive” alongside “dazzling” and “brilliant”.

This was, of course, the architect of the American foreign policy that Pilger blamed for atrocities all over the place. According to the Guardian, Kissinger’s contempt for human rights led him to “give the nod to Indonesia's military dictator for the invasion of East Timor, to condone the actions of the apartheid regime in South Africa in invading Angola, and to use the CIA to help topple the elected government of Chile”.

Nor was the Times blind to the great diplomat’s faults: “Kissinger was infamous too. He and Nixon bombed neutral Cambodia and helped to propel that country into a singularly awful civil war. They encouraged General Augusto Pinochet's overthrow of Salvador Allende's democratically elected leftwing government in Chile: "I don't see why we have to let a country go Marxist just because its people are irresponsible," Kissinger said. They abandoned the Kurds of Iraq, and connived in acts of violent repression by allies such as Pakistan, Indonesia and Iran. Kissinger's many critics called him a war criminal. Like Nixon, he was vain, furtive, manipulative, duplicitous and paranoid.”

He may have been obsessive, blinkered, brainwashed, a leftwing dupe, call him what you want. But even through the eyes of at least some at the Times, Pilger wasn’t all wrong.

The nature of bias

And what about the central charge of bias? Is that a terrible sin for a reporter? My instinct is to say “yes”. But that’s too simplistic.

A journalist should approach the job with an open mind, but that would be to negate the value of experience. If you know from years of observing and reporting that certain people are likely to behave in a certain way, it would be naïve and a waste of your knowledge to go into similar situations without some rational expectation of the way things are likely to turn out. The trick is to recognise when things aren’t evolving as they have in the past (see plane crash reports below) and to bring together what you know and what you are seeing now to explain to your audience what it all means.

Similarly, anyone watching events unfold over decades – whether in domestic political life or on the world stage – will form opinions as who should be pitied and who should be accused. It’s unavoidable. No one has any difficulty in recognising that people starving in Africa, whether through crop failure or governmental malfeasance, are victims who need help. Bringing those stories to the wider public is important. So is looking into the causes – and possible remedies. And these can spread very broadly indeed. If a government is failing its people, is that due to inherent corruption or incompetence or some outside influence? Finding out means looking at all sides of the story – and that applies across the board, be it a story about a neighbours’ feud over an unruly hedge or geopolitics.

Do we berate TV sleuths like Roger Cook, who exposed rip-off merchants and official blunderers? He went after them, but he also gave them the chance to speak – sometimes at great personal risk. Was he criticised for bias and impartiality? After all, his reports were all pretty one-sided with a “villain” in his sights. No. Because he was on the side of the “good guys”.

The Western media are happy to accuse Putin (with a great deal of justification) of being behind huge amounts of suffering way beyond Russia, Ukraine and Syria, of poisonings, murders, the shooting down of the Malaysian airliner in 2014, yet Pilger is pilloried by some for pointing the finger at America for other horrors. We can all raise eyebrows at the way he exculpated some horrible people, but that doesn’t take away from the reality – as shown in the appraisals of Kissinger – that America’s hands are far from clean. And that, for a lot of the time, we are too keen on our “special relationship” to say so. The bigger charge against Pilger here is probably that he ignored inconvenient facts, that he did not sufficiently address factors beyond American policy when examining the causes of outrages, such as 9/11 and the Cambodian slaughter.

He was hardly alone in that. I’m constantly droning on about stuff our papers haven’t reported or have underplayed. He is also accused of having preconceived ideas about situations that coloured his reporting. Again, he was not alone.

All of our newspapers have reduced their investment in investigative reporting over the past 30 years. It’s expensive and time-consuming. When they do deploy their depleted troops, it is rarely to go at a subject based on an unexpected tip or a chance chat in the pub. “Investigations” these days tend either to follow a scandal that has blown up out of nowhere (or been unearthed by a television team) or to pursue an agenda, political or otherwise. They need to have a very good idea of where they might end up or what they hope to achieve before they start.

When Mail executives ask Guy Adams to investigate Keir Starmer, do they expect him to go in with eyes wide open in innocence? If he were to return with tales of undreamt-of altruism, of secret philanthropy and general saintliness, would they throw open the first half of the paper to tell readers how wonderful the Labour leader is? Well of course that’s not going to happen. Starmer, we can be pretty sure, is no such saint. The question is, why would Adams be investigating Starmer in the first place? (I think we can assume, in an election year, that he is already well on the case.) He might set out with an open mind, but he would have an expectation of what he might hope to find and you can bet it wouldn’t be helpful to Labour’s cause. The author and the publication hold the clue as to what you’re likely to get. And so it was with Pilger.

As a documentary maker for television, Pilger will have been bound by rules of impartiality, rules that led to repeated clashes over questions of balance. But newspapers and independent film-makers have no duty to be impartial. Campaigning journalism – for which most news organisations congratulate themselves – can never, by definition, be impartial. So, it ill behoves those who enjoy the freedom to beat their own favourite drums to castigate others for doing the same.

Bias is sometimes unavoidable. Preconceptions, though. Very dangerous for any journalist. Even one as great as Pilger.

Post Christmas Regulars

# 1: January diet

Enough of all that. We’re still technically in the Christmas season, although we’ve moved from the feasting to the fasting phase. Yes, dieting is back on the front pages. The Sun and Mirror were both straight off the blocks on New Year’s Day with their trusty flab fighters Joe Wicks and Slimming World. Expect the Mail to follow in the next week or two once the last of the turkey has gone down.

That’s as far as I’m going with predictions, having fallen at the first hurdle. Last time, with Kate on 98 front-page appearances, I was betting the house on her hitting the century by Christmas. So much for paying off the mortgage yesterday (yippee!). She crept up to 99, courtesy of a Christmas Eve puff in the Sunday Express, but had to wait until Boxing Day to reach her final tally of 102 for the year.

You may have been under the impression that I thought she was ubiquitous. Maybe I did. But it turns out that was barely a third of her total for 2022. That survey did, to be fair, include the Times, Telegraph and Guardian. But they would definitely not account for an extra 200-odd smiley faces. It’s clear everyone needs to pull up their socks and get back on the case this year.

# 2: New Year’s Honours List

The other new year shoo-in is the honours list. And this year we had two. Whooppee! Here was a super bonus with Liz Truss doling out a gong for every four and a half days in office yet, amazingly, some seemed to think a nine-year-old amputee getting a BEM for highlighting child cruelty was bigger news. Or the woman made a CBE after campaigning against domestic abuse.

Or the failure to knight Kevin Sinfield and Rob Burrow for their work to raise money to help motor neurone disease sufferers (they had to make do with CBEs). The Mirror coupled its anger about the latter with its fury at “gongs for Tory fatcats”, but in the spirit of seasonal goodwill, let’s put the others down to compassionate news values rather than deflection.

The Telegraph and Guardian both played to their audiences with tried and trusted celebs – Jilly Cooper and Michael Eavis – while the Express took an unexpected turn with the headline “Let’s give more gongs to our unsung heroes”.

This was based on Esther McVey calling for the public to help identify “extraordinary and deserving unknown heroes who might have gone unnoticed”. There is, in fact, a mechanism for this and it’s the reason why local stalwarts do get their BEMs and their MBEs (rarely anything grander). Still, it’s a worthy sentiment. If only the paper didn’t then go on to list all the celebs and politicos who had been rewarded and fill the top half of the front page with a montage dominated by Shirley Bassey, Paul Hollywood, Jilly Cooper and Tony Blackburn. Nine-year-old Tony Hudgell BEM is there in the corner, but he doesn’t get a mention in the text until the turn. Ditto Rizwan Javed, who saved 30 people from suicide on the London Underground, and teenage charity fundraiser Louis Johnson.

Perhaps if the Express put such people at the heart of their coverage, rather rely on the familiar names, the honours might have a bit more meaning.

Missing the miracle

There are certain stories that we are so used to telling in a particular kind of way that some of us are in danger of missing the real news angle. People suing for libel and losing are almost always “facing financial ruin”, even if they face the bigger peril of going to jail for perjury, for example.

Plane crashes are a prime case in point. We are almost programmed to report on the number of dead, even if the (usually much smaller) number of survivors is the more unusual factor. The Mail is the only paper in Fleet Street that can be relied on never to fall into this trap.

And so it was yesterday when the top half of its front page was the dramatic picture of the blazing airliner in Japan with the headline “New year miracle on the runway as 379 escape inferno”. Metro did even better with its almost-full-page splash “We escaped from hell”. The Guardian got it right, too, with a big picture and the heading “We’ve seen a miracle 379 passengers and crew survive jet crash”, while the i made it a puff. Cheers all round.

The Sun was more interested in teenage darts sensation Luke Littler (who even made the Guardian front on Tuesday and again, in common with everyone else, this morning) and the Mirror in the Horizon post office scandal (memo to editors: if your splash headline contains the word “still”, especially if it’s in caps, underlined or in a different colour, it means you are raiding the files – or in this case piggy-backing on a TV show – instead of finding something fresh). The Telegraph preferred a not-very-compelling photograph from above of the woman jailed for running over her partner. But all those were matters of editorial judgment of what would be most interesting to their readers. Each to its own.

I can find absolutely no explanation for the blindness of the FT and Times, which both saw the value of the Japanese photograph and completely missed the key aspect of the story. First the FT:

“Airport crash Japan struck by second disaster”. A plane has burst into flames after a runway collision. It’s the second disaster in two days for the country. Five people have died. It’s only in the third sentence of the second par that we learn that 379 people emerged virtually unscathed.

And then the Times, which absolutely takes the biscuit. No headline, just a caption: “Runway crash A Japan Airlines flight to Haneda airport, Tokyo, with 379 passengers and crew, collided yesterday with a coastguard aircraft, killing five people. Pages 6-7”.

Regardless of how fine the material on pages 6 and 7 – and it wasn’t bad – that front-page caption showed such a lack of awareness of what is news that I despair. I really do.

Front page of the fortnight

I thought this pair on successive days from the Sun were clean and compelling pages to present its exclusive interview with the lad who resurfaced five years after vanishing with his mother.

Liz Gerard’s Notebook is a fortnightly column published in the InPubWeekly newsletter. To be added to the mailing list, enter your email address here.