Digital publishing spawned a new language for journalists to learn. How many of us sixty-somethings thought we’d be talking about engagement, Tweetdeck, Facebook Lives or web analytics as part of our everyday life in the newsroom?

But an older, stranger language – one that was unique to the analogue newspaper and with its roots in the hot metal era – has been rendered virtually obsolete by changes in technology, and is now all but lost. I find that sad.

Why shed a tear over old terminology? Change happens, the world moves on. Well, because this peculiar language encapsulated 100 years or more of our industry. For generations of journalists, commercial staff, typesetters, compositors and press crews, this was our lingua franca.

I dredged my memory for those weird terms I learned in my twenties, but soon ran out of gas. So, I posted on the Horny Handed Subs of Toil Facebook page, a kind of online care home for sub-editors of my vintage, to ask for help. Three hundred and sixty eight comments later, I have a substantial but still far-from-exhaustive list.

With enormous thanks to everyone who contributed to the Facebook thread, and for sharing their newsroom memories and some funny stories, here is my compilation of (some of) The Lost Language of Newspapers.

A

- Add – Additional text, sent after a story has been filed. Near the top of sub-editors' and compositors' hate list.

- Attic / hamper – Story across the top of the page, above the main page lead.

B

- Backyard – The second lead (most prominent story after the splash) on a broadsheet newspaper page.

- Banner – A bold, single-line headline.

- Basement / anchor – Story across the bottom to ‘hold the page up’.

- Bastard measure – Width of type that’s not a single column or a multiple of it (eg. 1.25 or 1.5 columns). This provided a subtle visual variation for the reader and “stopped the text looking like a string of washing”, as an old chief sub of mine used to say.

- Banging out – The tradition of compositors and journalists banging mallets on the stone (see below) as a farewell to a staff member as they finished their final shift before leaving or retiring.

- Bill / news bill / contents bill – Four- or five-word summary of a story that was interesting enough to be posted outside newsagents’ shops to stimulate sales of the paper. Immortalised on the cover of feature writer Roger Lytollis’s excellent memoir Panic as Man Burns Crumpets.

- Blind turn – When an article reaches the bottom of a column on the end of a paragraph, leading the reader to believe the story has ended when in fact there is more in the next column. To be avoided.

- Block – A photograph or, more accurately, the piece of metal the photographic image sits on. The original blocks were made of wood, hence the name.

- Blob par – A single-paragraph story, beginning with a black blob, tacked on the end of a larger story, to which it relates in some way. In today’s money, a bullet point.

- Blurb / boost / plug / puff / flannel panel – Front-page promotion, pointing to the choicest content inside that day’s edition. Also used on inside pages to promote next-day content.

- Book / dummy / flatplan – A miniature (about A5) layout of the next day’s edition, showing the pagination and the shape and size of advertisements, around which the editorial team place their content.

- Bromide – From the cut-and-paste production era of the 70s and 80s, a story printed on photographic paper, the reverse of which was waxed to enable it to be stuck on the page in the composing room. Missing bromides could often be found stuck to the sole of an unsuspecting sub-editor's shoe.

- Bust (or burst) headline – A headline which, when typeset, is too wide for the allotted space. A badge of shame for the guilty sub-editor.

C

- Catchline – One-word title given to a story by the reporter, as a unique identifier. Typed into the top right-hand corner of each sheet of copy paper and numbered sequentially, the catchline should be relevant to the story (eg. murder 1, murder 2, murder 3 etc). Certain words were banned: eg. ‘catchline’ (because everyone would use it) and ‘kill’ (because that term is used as an instruction to kill a story).

- Carbon or ‘black’ – A copy of a news story. Reporters would insert two pieces of copy paper into their typewriter, with a piece of carbon paper in between to make a copy, in case the original was lost or damaged in production or there was a subsequent legal query.

- Casting off – The art of estimating the length of a story, taking into account type size and column width, so that it fits snugly into the space allocated for it. A key tool in the analogue sub-editor’s shed.

- Change page – A planned, editionised update for the next edition to freshen the news or to incorporate stories from a particular locality.

- Chapel – The union membership within a single workplace. The National Union of Journalists and the print unions (the NGA, SOGAT and NATSOPA) would each have a chapel in every newspaper office.

- Chase – Steel frame designed to be tightened to lock the type in place when a hot-metal page was complete. As late as 2018, the Daily Express and Daily Star subs still referred to the edition being ‘locked’ - decades after the chase had been thrown on the scrapheap.

- Chinagraph – An extra-thick wax pencil used by sub-editors to mark photographic prints, showing the crop they wanted. Easily wiped off afterwards, and usually red, in my experience.

- Copy boy – Teenagers employed to carry copy (news and sports reports) from the copytakers (copy typists taking dictation from reporters over the phone) to the news and sports desks. Very occasionally, there was a copy girl.

- Copy paper – Paper on which reporters typed their stories. Cut from the waste newsprint (the stuff papers are printed on), a sheet of copy paper was roughly 7 inches wide and 5 inches deep (17.5cm x 12.5cm). The intro stood alone on the first sheet, with two or three paragraphs per sheet thereafter.

- Copytakers – A bank of typists, wearing microphone headsets, who took reports over the phone from journalists in the field. A reporter might think about wrapping up their piece when the copytaker asked: 'Is there much more of this?'

- Copytaster – A journalist whose job was to read (‘taste’) all incoming stories and decide which of them should be published and their relative prominence in the paper.

- Creed room / wire room – Communications hub where typed messages were sent and received from external locations via a teleprinter. Some teleprinters produced punched tape, for data storage.

D

- Deck – Depending on where you learned your craft, a deck is either a single line of headline (eg. a four-deck headline has four lines) or a term to describe the whole headline.

- Delayed drop / dropped intro – Unlike the standard news formula, where the nub of the story is summarised in the first paragraph, the delayed drop starts the story slowly and gets to the point only after several paragraphs. Under legendary editor Sir John Junor, the old broadsheet Sunday Express turned the delayed drop into an art form.

- Dis – To throw away a story that had been typeset in hot metal (presumably derived from dismantle).

- Dog’s cock / dog’s dick / screamer / shriek – An exclamation mark on the end of a headline.

- Drop cap – An oversized initial letter at the start of an article.

- Dummy edition – A not-for-distribution prototype of a new or redesigned paper.

E

- Ears / earpieces / lugs – Small, premium-priced advertising positions at the top left and right corners of the front page.

- Em (mutton) / en (nut) – A measure of type width, based on the letter m and the letter n. In hot metal days, sub-editors would mark stories to be typeset ‘nes’, meaning a nut (or en) indent on each side of every line of type. This had the effect of building in white space between columns.

- ‘Ends’ – Typed by the reporter at the end of each story, to signify it is complete.

- etaoinshrdlu – A phrase Linotype operators would set when they had made an error. The letters were the first two columns on the left hand side of the Linotype keyboard, which was organised by descending letter frequency to speed up the operation of the machine. It was far from unknown for etaoinshrdlu to find its way into print.

F

- Filler – Short (one- or two-paragraph) stories sent to the composing room to fill a hole, in case the planned content fell short.

- Flong – A flexible, papier-mâché mould which takes an impression of the forme (the flat, metal page assembled by a compositor). From the flong, a semi-circular metal stereotype is cast, for use on the rotary press.

- Forme – The final, made-up page as it leaves the composing room, with all the type within the chase and locked in place.

- Fudge / fudgebox / box / slot – A device that enabled late-breaking news to be printed without stopping the press. A Stop Press column on the front page would be left blank so stories that broke after deadline could be ‘fudged’.

- Furniture – Editorial content that appears in every edition but isn’t news, features or sport (eg. puzzles, horoscopes, index panel).

G

- Galley – Metal holder for carrying type around the composing room.

- Galley proof – A proof of a single story, taken from a galley. Key content requiring special attention, such as the comment column, would be checked from a galley proof at the earliest opportunity, rather than waiting for a page proof to be pulled.

- Gash copy – Random content used as a placeholder on a page until the intended content - usually a late-breaking story - was available.

- Gash page / spill page – A page filled with editorial content that could be ditched to make way for late advertisements or an overspill of copy. Often, this was the Births, Marriages and Deaths page, as death announcements were accepted until very close to deadline, or the final editorial page before the classified section.

- Grant machine – A projector the size of a phone box used to magnify or reduce artwork and project on a light box so an image could be traced off. (Hat tip: Mike Dempsey’s blog. I was never really sure what it did).

H

- Hanging indent (aka 0&1) – Where the first line of each paragraph is set across the full width of the column and the subsequent lines are indented left. A device used to add an element of white space to the page.

- Hot metal – A mixture of molten lead, tin and antimony used to create lines of type on a typesetting machine. The molten metal sat in a pot at the rear of the Lino machine.

- H&J – Hyphenate and justify. Arranging (justifying) type into lines of uniform width, using hyphens to break words where necessary.

K

- ‘Kill’ / ‘Must kill’ – An instruction to take a story out of the production process, often for legal reasons.

- Klischograph – Mechanical engraving machine used to scan photographic prints and convert them into zinc images.

L

- Lamson tube – A system of pneumatic tubes that fizzed plastic capsules containing editorial copy around the building at high speed, primarily from the editorial department to the composing room. Powered by compressed air, Lamson tubes were also used in banks and department stores to move cash around the building.

- Leading – Spacing between lines of type. Blank pieces of lead were used to stretch an article that had fallen short of its allocated space in the page.

- Linotype machine – Invented in 1886 and still in use 100 years later, the Linotype machine set type a whole line at a time. This revolutionised newspaper production - until then, type had been was set by hand, letter by letter.

- Literals – Mis-spellings or typographical errors.

- Ludlow (Typograph) – A machine for setting type in larger sizes, such as headlines. The Linotype machine only went up to 24pt, which is where the Ludlow took over.

M

- Masthead / Titlepiece – The newspaper’s title, as displayed on the front page or on top of the leader column.

- Mother / Father of the Chapel – Union leader at the local business level, equivalent to a shop steward or convenor.

- More / mf / mfl – Used by reporters at the end of each piece of copy paper to signal that there is more to follow / more follows later.

- Mutton dash – The standard width of a dash was the width of a letter m (aka ‘em’ or ‘mutton’) in whatever type size was being set at the time.

N

- NIB – A ‘news in brief’ single paragraph story.

- Nun's fart – Inappropriately weak typeface, eg. light sans with little impact. (Courtesy of @TimMinogue. A new one on me, deserves to be spread far and wide).

O

- Off-stone time – The deadline for a page and / or complete edition to be finished in the composing room and sent to the next stage of the process.

- Orphan – First line of a paragraph that appears at the foot of a column or page. To be avoided. A minimum of two lines is preferable, to carry the reader over to the next column.

- Overmatter – Material that has been typeset but isn’t needed for the edition.

- Overnights – The inside pages for the next day's edition of an evening newspaper, written and subbed in the afternoon, after the on-day edition was finished.

P

- Page furniture – The non-editorial material that appears on every page (eg. the folio / dateline and advertising).

- Printer’s pie – When a galley or a whole page of type is spilled on the floor. Usually accompanied by a large side order of bad language.

Q

- Quoins – Metal wedges used to lock type in place in the chase.

R

- Rag out – A story from the newspaper’s archive, used as a graphic, with ragged edges to make it look like it has been torn out of the paper.

- Ragged right – A device for adding white space. The left-hand side of the story is justified (‘flush left’) but the right-hand side is not, so it looks ragged.

- Random – Area of the composing room where the sections of a hot metal story which had been set by a number of different typesetters would be assembled. Items of page furniture, such as the masthead, page headers, columnists' logos, were stored on the random.

- Runner – A live sports report from the stadium. Written 'back to front' - the reporter files the team news and some colour (weather, pitch condition, the teams' current form), then a description of the match in several short takes, and finally the intro, distilling the outcome. This was the standard modus operandi for Saturday sports editions up and down the country - the much-loved Pink 'Uns and Green 'Uns. Still in use today but much less widespread.

- Running turn – Where an article reaches the bottom of a column in mid-paragraph, naturally leading the reader’s eye on to the next column. Warms the cockles of even the most miserable sub-editor’s heart.

S

- Seal – Usually white on red and placed at the top, right-hand corner of the front page to denote the edition (e.g. Midday, City, Late Night Final).

- Set and hold – Instruction to typeset an article not yet placed in the paper and to hold it in the composing room pending further instructions. Often used for pre-written obituaries. Nothing to do with hairdressing.

- Shadow box – A ruled box around an article, with two adjoining sides having slightly thicker rules, producing a 3-D effect. There was much debate in the Bradford Telegraph & Argus newsroom about which sides the shadow should fall, until the chief sub decreed: ‘At the T&A, the sun always shines from the top left.’ (i.e. the thicker rules should be on the right-hand side and the bottom.

- Short – A story that's longer than a NIB but no more than 150 words. Often used to fill planned single-column slots on the inside or outside edge of the page. Newsdesks would often have two wire baskets, one marked Shorts, the other Tops (see below).

- Slip edition – An unplanned edition change, to accommodate breaking news or correct a howler.

- Slug – A single line of hot-metal type.

- Smalls – Small classified advertisements, such as Items for Sale. Fiddly to typeset, it was a job often given to the most skilled compositor on the staff.

- Spike – A brass spike set in either a wooden or metal base, on which news editors spear stories that are not up to publishable standard. Reporters hated having their work ‘spiked’. The spike also claimed many human victims, who spiked their hand (or other part of their anatomy) rather than the copy. If computerisation hadn’t made it redundant, the Health & Safety at Work Act surely would.

- Squeeze to fit – If a story was fractionally too long, the compositor employed a device to crush the lines of type together. This always felt like cheating.

- Starburst – Device popular in the 1970s, often white on black or a garish colour combination, used to highlight content such as prize competitions. Designed to catch the reader’s eye, liable to burn the retina. Not to be confused with the fruit-flavoured sweet of the same name.

- Stick – A small galley, about six inches long. ‘Give me a stick’ meant: ‘Write about six inches-worth of copy’.

- Strapline – Subsidiary headline that straddles the top of an article or feature spread.

- Stone – Long, flat metal tables in the composing room, where stories were made up into pages.

- Subdeck / subhead – Subsidiary headline that sits below the main headline on an article.

T

- Take – One sheet of copy paper containing editorial material. When time was tight, a news editor would bawl at the reporter: ‘File it in takes.’ (ie. give it to me one sheet at a time) to help speed up the production process.

- Thicks and Thins – The thickest and thinnest of the available strips of lead used to space out stories that fell short in the page.

- Top – Any story above 150 words. The more important stories, to be given greater prominence.

- Trannies – Colour photographic transparencies.

- Type sizes (and their wonderful names) – When I was at the Daily Express (1979-85), the standard style for inside page leads was: Intro in Pica (12pt), second par in Long Primer (aka LP, 10pt), third par in Brevier (9pt), rest of the text in Minion (8pt). Others included Bourgeois (9pt, pronounced ‘Burjoyce’) and Nonpareil (6pt, known universally as Nomp), which might be used for data-heavy content such as sports results, to minimise the space they took up. The smallest type sizes – Ruby, Pearl and Diamond, might be used in some classified adverts but never in editorial, at least not on the papers I worked for.

- Typescale / em rule – Ruler marked with the most common point sizes, used for measuring type and sizing pictures. The Reproduction Computer (aka picture wheel) was also used to size pictures.

W

- Widow – A line of type which falls at the top of a column and is less than the full width. Poor typography, to be avoided.

- WOB / Reverse – White on Black (i.e. white type on a black background) Cousins of the WOB were BOTs (black type on light-grey background) and WOTs (white on dark-grey).

X

- x-height / ascenders / descenders / beard – The x-height refers to the height of the lower case letter x in any particular font. It determines how large or small the typeface looks. In general, the bigger the x-height, the more readable the font. An ascender is the portion of the letter that rises above the x-height (b, d, f, h, k, l and t have ascenders). A descender is the part below the x-height baseline (g, j, p, q, and y). The beard is the area between the x-height and the top / bottom of the ascender / descender. As we're now well into the weeds of typography, I think I should end it there.

However..

There’s an offshoot of the lost language that's worth mentioning – those words that only journalists use or that mean something different when used by a journalist rather than a ‘normal’ person. Here are a few (normal person’s definition first):

- Pledge – A brand of furniture polish / Promise.

- Snap – Sharp breaking sound / Sudden outbreak of chilly weather (as in ‘cold snap’).

- Vow – What you take at your wedding / Promise (or pledge).

- Probe – (i) An invasive medical procedure or (ii) An unmanned space vehicle / An investigation or just someone asking a few questions.

- Saga – (i) Epic Norse tale or (ii) Holiday company exclusively for older people / Long-running story that’s starting to bore me.

- Spat – Past participle of ‘to spit’ / An argument.

- Quiz – Fun way of spending an hour at the pub / To question (as in ‘Police are quizzing a suspect’, which conjures up the image of the suspect being asked questions on general knowledge, geography, music and sport, and finishing off with a picture round).

- Bid – A price you’re willing to pay for an auction lot / An attempt.

- Audacious bid – A ridiculously low-ball offer made by Newcastle United for a player they have no intention of signing, just to appease the fans / Same. (N.B. This was written when miserly Mike Ashley was still running the show at Newcastle).

- Blow – What you do when your tea’s too hot / A disappointment.

- Plump – Adjective meaning slightly overweight / Verb meaning to choose (frequently found in restaurant reviews, as in ‘my partner plumped for the prawn cocktail).

- Posed – What photographic models do / Asked.

- Revellers – A word that normal people never use / People out on the town, getting hammered, while I’m stuck in the office having to write about them.

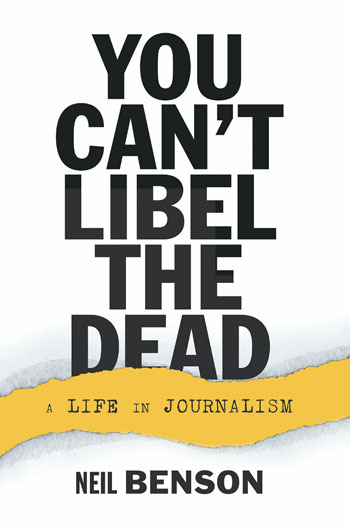

You Can’t Libel the Dead: A Life in Journalism, by Neil Benson, is published by Takahe Publishing, priced £10.95.