In his paper-strewn office at his homely bungalow in the heart of the glorious Derbyshire Dales, Gerry Kreibich digs out his 1989 application for voluntary redundancy after 18 years as a journalism trainer at the long defunct Richmond College of Further Education in Sheffield.

“I feel I have always been more journalist than lecturer with the result that tertiary fails to challenge or stimulate me. I would appreciate the chance to switch my career while I still have the time and energy,” reads the yellowing letter.

“It wasn’t forced on me but circumstances created it,” recalls Gerry today, 34 years on from his decision to leave the South Yorkshire college which helped shape the careers of thousands of journalists – including Jeremy Clarkson, sports broadcaster turned spiritual preacher David Icke, former BBC star David Shukman and countless others throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

That letter – and his rationale for leaving a job he had loved over nearly two decades – sums up the career and mindset of a newspaperman turned lecturer who was always a journalist at heart. And even at 90 years of age, still is…

“I retired at 55. I was enjoying the job and I would have continued to normal retirement age but there was a big reorganisation of further education. We started getting letters to say they were introducing tertiary education.

“Further education colleges were being given a totally different responsibility and they wanted us to do other things as well, such as English. It was a whole reshuffle of further education – 18 of us left, all in top positions throughout the college.

“And what could I do, immediately at 55? I could do stories for the Matlock Mercury or the Derby Evening Telegraph – there were endless opportunities as a journalist.”

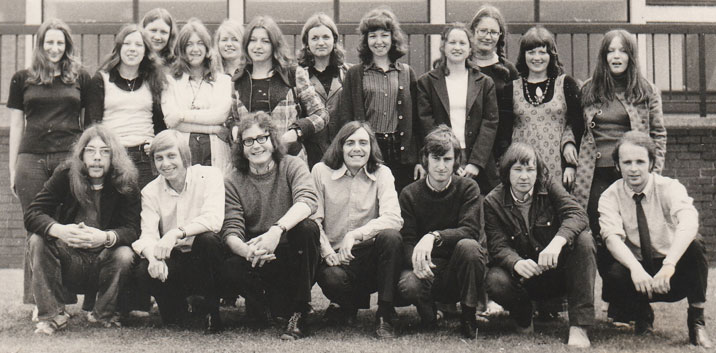

Nearly three and a half decades may have passed since Gerry took early retirement from journalism lecturing but his name will still resonate today with many from the legions of trainee hacks who once soaked up the basics of shorthand, law, public administration and the art of story-getting – as well as the universal art of enjoying life away from the parental home – at the college on the hill in suburban Sheffield.

Three funerals & two weddings

At 90 years of age, Gerry can offer a highly distinctive bygone – and contemporary – perspective on a trade which has undergone a tumultuous transformation since his days in the early 1950s as a rookie reporter with the Warrington Guardian series – where after collecting wedding and funeral forms he would cycle off every Monday morning to interview newly bereaved widows, sometimes with the corpse in attendance in the very same room.

“You would ring every vicar and funeral director. They would say ‘there are three deaths’, and they would give you the addresses. So, I would think I have got three funeral houses to go to and a couple of weddings to cover. I used to see two or three corpses a week because they had them at home.”

After completing his National Service, Gerry landed a job as a court reporter with the long gone Manchester City News, where he saw convicted murderers sent to the gallows by judges who donned black caps as they passed sentence. “It was fascinating; all the accused seemed to be friendly, amiable chaps. There would always be relatives in the courtroom, who would shout ‘No, No.’”

Gerry eventually left behind the corpses, grieving widows and condemned murderers of Manchester to set up home with wife Una in the tranquil surroundings of Matlock Bath in Derbyshire where he had worked as a reporter on the local weekly, the Matlock Mercury, before leaving for a stint as a sub-editor on the Newark Advertiser in Nottinghamshire.

But the Kreibichs had fallen in love with the Derbyshire Dales and Gerry was delighted to be asked to return as editor. “I was thrilled and honoured to be asked to come back as editor by the owner, an eccentric woman called Ella Smith, who had started the paper in the first place years before.

“It was 1962-63, I would have been around 30. The paper was made up on the premises, flatbed on the stone, hot metal with a couple of linotype machines. It was saturation coverage in Matlock, a circulation of around 8,500 – it was such good fun, the best job I ever had really. Editing a small weekly, everybody knows who you are, everything interests you, you walk through the town and you think, that’s nice, I will do a piece on that. You make a big difference to people’s lives.”

Gerry eventually left the editor’s chair on the Mercury “for three quid a week more” as Matlock district man with the Chesterfield-based Derbyshire Times, where he would meet fellow reporter Ron Eyley – and life would ultimately take an enthralling new twist.

Destiny beckons

“Looking back, it was the biggest single moment. I am fascinated by the way all life is chance.”

His former colleague Ron had, by now, left the Derbyshire Times to become a journalism tutor at Richmond College in Sheffield in the very early years of NCTJ pre-entry and block release college courses – and rang Gerry to ask him to join the UK’s new newspaper training revolution.

“It changed my whole life. The NCTJ courses had only been running 12 months – they were in their infancy and Ron said, ‘we are looking to take on another lecturer.’ I really fancied it – when I was editor of the Mercury, I had really got on well with the juniors, you would talk to them and encourage them.

“I was a bit worried about leaving newspapers but if you are going to leave, the ideal is going to an environment of newspaper people, helping youngsters to start. I thought it was blooming marvellous.”

Gerry entered the world of journalism training in September 1970 – and soon created an intriguing piece of UK journalism history with the launch of the Richmond Reporter, a weekly entirely written by NCTJ pre-entry students.

“I thought the only way of making sense of this is giving them the stuff to write, deadlines and all the rest of it. The Richmond Reporter started off modestly but optimistically on October 7, 1971. The idea was to provide an element of realism.

“We printed 200 to 300 a week, there were people in the corridors buying them at 2p. We would say to somebody ‘go down into Sheffield and find out about so and so’. We could say ‘get a taxi’ because we had reporter funds from selling it. If that’s not realism, I don’t know what is.”

Gerry looks back on his days at Richmond as largely experimental times for UK newspaper training. “We were all guinea pigs; the six colleges [the further education sites which pioneered the NCTJ pre-entry and block release journalism training courses from the early 70s, at Sheffield, Darlington, Preston, Harlow, Cardiff and Portsmouth] were trying stuff out. Ideas that worked well, like one-par rewrites and the ‘find a story’ exercise, we kept and developed. Those that didn’t work, we just abandoned.

“The first week, the new students would all come in thinking there would be lectures like school and I would say, ‘right, get down into Sheffield and find a copper, a taxi-driver, a shop assistant, get talking to them, you will find they have got a story because there is a story in everybody’.

“It is no good having people wanting to be reporters if they daren’t go and knock on people’s doors and say can I talk to you for a minute.”

Gerry’s 18-year tenure at Richmond throughout the 1970s and 1980s would coincide with a golden era for newspapers – with mass circulations, well-staffed newsrooms full of specialist operators and newspaper vendors on city street corners selling a string of editions throughout the day – before the internet age and the inevitable rush to digital drove a coach and horses through the priorities of an entire industry, particularly at local and regional level.

Winds of change

And as the internet era ushered in new forms of journalistic endeavours – from an obsession with website hits to live blogs and listicles – in attempts to try and monetise digital as print circulations tumbled, so the training of journalists underwent sea changes of dramatic proportions with a proliferation of journalism and media studies degree courses at universities across the land.

As Gerry wryly recalls after more than 70 years as reporter, editor, lecturer, freelance, website owner and lifelong news junkie – he still gives the Matlock Mercury the occasional story tip: “We got a message that Sheffield University was interested in possibly doing journalism courses. Two lecturers came up and I said cynically that they seemed to be equally interested in how many students they would get at a few thousand a year.

“I honestly feel that it is an immoral set-up at the moment. The jobs don’t actually exist so they create strange topic titles and things. There are not as many reporters anyway; it is the public that miss out of course. Stories are not being covered because the journalists are not out there on the streets. You couldn’t count the number of non-appearing stories the world knows nothing about.”

While Gerry is no Luddite – he has embraced the digital world with his own website (www.teachingjournos.com) detailing the history of his days at Richmond along with many colourful memories of the lives of trainee hacks in the 70s and 80s – he is deeply saddened by the seemingly remorseless decline of print news.

“Has the Matlock Mercury got an office here? Have they heck, they haven’t even got an office in Chesterfield now. If you look at the Mercury, the address is a street in Edinburgh. I am just very sad.”

The man who once declared himself more journalist than lecturer may – like all of us who as teenagers rode the Richmond rollercoaster back in the 70s or 80s – be a creature of his times but his recipe for the essence of good journalism is surely still relevant to an increasingly beleaguered industry today.

“In my mind, journalism is a matter of asking questions, finding information and writing it in a way that is understood.”

This article was first published in InPublishing magazine. If you would like to be added to the free mailing list to receive the magazine, please register here.