It is imperative that scholars and students of media reporting, as well as citizens and governments, wake up to the reality that Covid-19 is not simply a deadly aberration temporarily wreaking havoc on the world. This is to mistake symptom for cause. Covid 19 is both expressive of and exacerbating today’s multiple, accelerating and mutually compounding global crises. We live in a world-in-crisis, that is to say, a world that has spawned existential threats of its own making and which now presage the collapse of human existence as we know it. These deepening and mutually entwining global crises include climate change, biodiversity loss, mass extinctions, food and water insecurity, financial meltdowns, forced migrations, humanitarian disasters, conflicts and wars, and yes, global pandemics too. World civilization, as we know it, is teetering on the precipice of terminal collapse. This must shape how we choose to approach and analyse Covid-19 in respect of its communication in the world of journalism and becomes the critical benchmark for the sorts of expectations that we have as concerned citizens for news handling of the global pandemic.

We live in a world that has spawned existential threats of its own making and which now presage the collapse of human existence as we know it.

In the beginning

Covid-19 has exerted a profound impact on individuals and societies around the world in addition to the global 1,062,624 deaths and nearly 37 million cases recorded at the time of writing. And it will continue to do so for the foreseeable future, not least because of the way in which it has interacted with and exacerbated other forms of global crisis. For example, in respect of how it has led to mass unemployment and economic recession, worsened global poverty and generated food shortages. It has also served to throw a torchlight on racialised inequalities including differential life chances and indeed the very chance of life / death itself for minority ethnic groups, based on i) their precarity within racialised job and housing markets, ii) the increased vulnerabilities associated with access to health care and personal protective equipment (PPE), and iii) morbidity patterns that derive from preceding structures and experiences of poverty.

Covid-19 has also become a vector for elite sponsored ‘Othering’ discourses.

“Othering” … and other by-products

Covid-19 has also become a vector for elite sponsored ‘Othering’ discourses, witnessed for example in the barely articulate outpourings and dog-whistle politics of current US President Trump. Words seemingly designed to sow seeds of division and dissimulate the incompetence and negligence of Covid-19 policy responses behind a wall of nationalist rhetoric and international scapegoating. Covid-19 has also variously impacted the climate emergency, temporarily, for example, reducing carbon emissions through reduced aviation, traffic and tourism and creating less pollution. For a time, it also noticeably improved air quality and made our cities more visible. And stories of more birds and different animal species venturing back into quieter cities have also been widely circulated online and elsewhere, reminding many of us of what has been lost in our usually frenetic and fossil-fuelled existence. But the pandemic has also temporarily stalled the mass protests against government inertia toward climate change, including those of Extinction Rebellion, Greta Thunberg and others that were mass mobilising before its emergence.

In these and in a myriad of other ways, Covid-19 has become entwined within our world-in-crisis, exacerbating the stresses and strains of synchronous global crises. There is an extensive and critically engaged research agenda here waiting to be developed by all those who are now waking up to the combined threats of a world-in-crisis and who are serious about exploring the deficiencies and deepening the potentialities of journalism. And in ways that can communicate to publics and politicians the dire risks that we now face as well as discuss and deliberate the responses now so urgently required.

Covid-19 has become entwined within our world-in-crisis, exacerbating the stresses and strains of synchronous global crises.

Not just another disease

There is growing evidence to suggest that Covid-19 cannot be assumed to be yet another unfortunate albeit particularly virulent and deadly virus mutation. As Herbert Girardet, consultant to the United Nations Environment Programme observes, “Covid-19 exposes the inherent fragility of our globally interconnected economic systems and the inequalities that they perpetuate. It is a global health crisis that is superimposed on a global environmental crisis – defined by climate change, biodiversity loss, soil depletion and chemical pollution.”

Covid-19 is not only exacerbating our world-in-crisis but is in fact expressive of it. The pandemic is another sign of the overshooting of human society’s insatiable demands on nature and, given the current perilous state of our ecosystems through relentless human exploitation and extraction, heralds further pandemics in the years ahead.

“How has the planet’s capacity overshot? As a result of intensifying human demands, with deforestation, biodiversity loss, extinction of species, and water crises occurring all over the world. Covid-19 is just the latest manifestation of a broken relationship between humans and nature, and bears witness to the transgression of the planet’s safety boundaries coupled with high-risk human behaviours, for example wildlife trade markets, intensive livestock conditions – which create favourable conditions for the emergence of zoonotic epidemics, which have been increasing over the past two decades.” (Antonelli, M. Riccardi, G and Valentini, R. 2020)

Along with other pandemics in recent years, such as Ebola, Avian Flu, and MERS, Covid-19 is a zoonotic disease that mutates and jumps species. Many scientists now think that its probable first host was bats, though possibly this new strain of coronavirus was bridged to humans by pangolins. Both these wild animals we know are trapped and transported and then caged, sold and killed in the unhygienic and crowded wet markets of Wuhan city, China – where the first outbreak occurred.

The UN’s Global Biodiversity Outlook-5 confirmed in 2020 that the international community has failed to meet any of its 20 biodiversity targets pledged in Aichi in Japan in 2010 and designed to slow the loss of the natural world. The recent increase in deadly zoonotic diseases, far from arriving out of nowhere, can be situated within the contemporary planetary emergency and the continuing devastating impacts inflicted by human society on animal habitats and ecosystems.

The pandemic is another sign of the overshooting of human society’s insatiable demands on nature.

A necessary research agenda

Now is the time to better understand journalism’s silences and seeming reluctance to both recognise and situate Covid-19 in today’s world-in- crisis. To see it as a global crisis that has not only been spawned by the contemporary global dis(order) but is now exacerbating it. To what extent, why and how has news media reporting around the world, both nationally and transnationally, diminished, distanced or entirely dissimulated Covid-19 as an integral part of our world-in-crisis? To what extent have journalists sought to join up the dots between the global crises of environmental de-spoilation, climate change and international inequality, conflicts and forced migrations or, if not, why not? To what extent are environmental externalities investigated, exposed and deliberated in news reporting of ecological collapse and biodiversity loss? To what degree, if at all, has indigenous thinking and traditional environmental practices been recognised in the mediated public discussion of and policy responses to today’s rapidly compounding crises of environment and ecology? These and other questions borne of our world-in-crisis have generally yet to be recognised much less addressed by today’s news media.

The recent increase in deadly zoonotic diseases, far from arriving out of nowhere, can be situated within the contemporary planetary emergency.

A world-in-crisis?

My concern is not only that it seems that most news media, with few / occasional exceptions only, are institutionally, professionally and culturally disposed to global myopia but that scholars and students of journalism may be also, preferring to view Covid-19 through national glasses and seen as a communicated public health crisis, albeit one shot through with government and political discourses that can unravel into full-blown political scandal and crisis if revealed to be mired in deceit and / or policy ineptitude. But when we approach Covid-19, as we must, in a world-in-crisis, so we must also set out to examine journalism’s emergent ‘global outlook’ and global reporting practices.

Journalism is pivotal to communicating the ‘enforced enlightenment’ that is now compelled on today’s ‘world civilization of fate’ by accelerating, intensifying and mutually compounding global crises – including Covid-19. These existential threats warrant collective actions by states, governments and citizens around the world, acting in concert and cooperatively for the benefit of all. Now is the time not only to expect but to demand that journalism helps us to see and better understand the indispensable relationship between human society and the planet’s ecosystems, biodiversity and climate and how this vital nexus is now fast breaking down, threatening not only the continuation of human life as we know it but the conditions for all life on planet earth. Covid-19 is a wake-up call to our world-in-crisis; it must be recognised and reported in such terms.

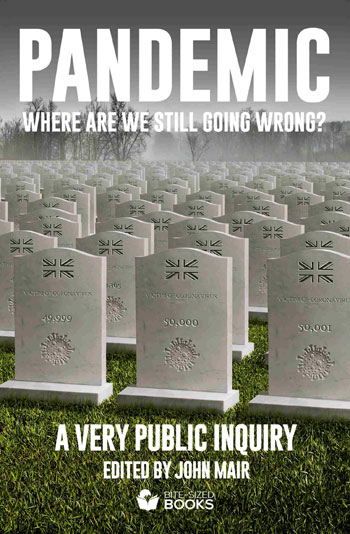

This is an abridged version of an article that appears in the new book ‘Pandemic: Where Are We Still Going Wrong?’, edited by John Mair and published by Bite-Sized Books.