Does it matter if readers, viewers or listeners don’t trust the journalists bringing them the news?

Is the Pope a Catholic?

A clutch of surveys ranking journalists with politicians and estate agents in the pits of public esteem and the general bashing of mainstream media on social media have revived the angst about how our industry can hope to survive unless it can rebuild its reputation.

In America, Google has decided to become the guardian of journalistic ethics with what it grandly calls its Trust Project, in which it urges news organisations to publish mission statements for journalists to disclose their backgrounds, levels of expertise and personal interests. The reward for those that do might be preferential ranking in search results.

Is this what readers want? A potted biography with every snippet of news? (Yes, InPublishing does exactly that on features such as this, but it doesn’t trouble you with correspondents’ leisure activities or A-level results.)

In this country, we’ve had four years of hand-wringing and wrangling over press regulation since the phone-hacking scandal erupted. Now the government has its sights on the BBC, regularly accused of left-wing bias and uncompetitive behaviour - largely by competitors from the right. As an industry, we have been roundly told to clean up our act, and opinion polls showing the public’s lack of trust in us are used to bolster that argument.

With newspaper circulations plummeting, what further evidence do we need of the price we are paying for losing people’s trust?

Except we haven’t. Lost people’s trust, that is. Journalists have always been below the salt. In fact, according to Ipsos MORI, people seem to be more willing to trust journalists to tell the truth today than at any time since 1983.

To be fair, only 22% of people questioned in the pollster’s last such survey said they would trust journalists – hardly a ringing endorsement – but we were still ahead of politicians, who scored 16%.

The fact is, politicians, estate agents and journalists have always swum along the bottom of these charted waters. People still vote, though in fewer numbers; people still buy and sell houses; people still read, watch and listen to the news, though they may do so on their computers or mobiles rather than in newsprint or on television or radio.

Both MORI and YouGov frame the questions for their trust polls in similar terms. MORI asks “Do you trust xxx to tell the truth?” while YouGov asks “How much do you trust xxx to tell the truth?” offering options of ‘a great deal’, ‘a fair amount’, ‘not much’ or ‘not at all’. In both, doctors and teachers routinely rank at the top.

It is perfectly possible to argue that what you are printing is true – but if you tell only part of the story, you are not printing the truth.

Personal experience

These are, of course, the very professions with which most people have had direct contact and so their opinions will be based on personal experience rather than perception. Journalists’ poor showing may also be the result of personal experience – that dread question we hear every time we are introduced to someone new: “Why is it that whenever papers write about something I know about, there is always something wrong?” Heaven knows, but it’s true and journalists notice the same phenomenon. But that doesn’t make us untrustworthy individuals, just prone to human mistakes.

Besides offering interviewees different levels of trust, YouGov asks separate questions regarding BBC, ITV, broadsheet, mid-market and redtop journalists, as it does with Conservative, Labour and LibDem politicians. The politicians all get much the same ratings, but BBC and ITV journalists score highly – around 60% - while redtop journalists come right at the bottom, barely reaching double figures.

Richard Sambrook, director of Cardiff University’s journalism centre and for many years a BBC executive, thinks the difference may in part be explained by the fact that we accept television and radio journalists in our homes: “The public have always had a low opinion of journalists - it's nothing new. There has tended to be a gap between newspaper journalists and broadcasters where broadcasters were more trusted, but that is closing. I think the reason for that was that people invest trust in people they can see and hear more. Plus broadcasting is regulated which some surveys for Ofcom have shown the public recognise and value.”

Susie Boniface, who writes for the Mirror as Fleet Street Fox, agrees: “It’s been ever thus, it’s just that there’s a justifiable excuse for it now, post-hacking. However, as with politicians, any drop in trust means people see no reason to rely on you anymore. The phones stop ringing, the lawyers get called in quicker, the leaks don’t happen. I think there are plenty of good journalists doing good work and most people realise that. I hope that the phone-hacking effects are reducing as the good guys keep plugging away and the bad guys keep getting caught.”

Subbing is a dying craft and neither editors nor managements care a fig about subbing anymore.

Echo-chamber

While it probably doesn’t make much difference whether people believe journalists generally, it does matter that they trust the newspaper they read or the network they watch. And the evidence is that they do – if only because their choice of newspaper is likely to reflect their own opinions.

Coverage of the migrants gathered in Calais is a case in point. One paper’s asylum seeker is another’s illegal immigrant; one paper’s group of desperate people is another’s marauding mob. When Robin Lustig used his Huffington Post blog to try to balance what he saw as one-sided reporting with “some facts”, more than 800 people piled in to bombard him with counter “facts” almost certainly gleaned from newspapers or television.

Sambrook says: “People are more suspicious of agendas than ever and are able to fact check independently. So the logical conclusion should be that they will ‘see through’ media agendas and manipulation - for example over migration - and desert the press. But they're not really. The Mail is still hugely successful, the Sun still sells stacks.

“Because one of the paradoxes of lots more information and the ability to find out for yourself is that people seek refuge in views they agree with. It was always the case, but is now more so than ever, I suspect. People buy the Mail because they agree with it and want their views confirmed - the ‘echo chamber’ effect or homophily as we academics call it.”

All of which doesn’t mean that everything’s hunky dory. Far from it. The BBC is required to be impartial; commercial operations such as the Mail, the Sun, the Times and the Guardian are not. They have every right to pursue their own agendas, but there have been too many instances of inconvenient elements being left out of stories, of wildly inaccurate splashes being “corrected” weeks later in a paragraph at the foot of page two.

These may not influence the trust ratings by more than a percentage point or two – redtop journalists’ YouGov score fell to a low-point of 6% at the height of the hacking scandal in July 2011 but had bounced back to the standard 10% by the end of the year – but they do raise questions of a worrying lack of integrity. It is perfectly possible to argue that what you are printing is true – but if you tell only part of the story, you are not printing the truth.

Trust is not the problem. Poor journalism is the problem.

Emily Bell

Poor journalism

As Emily Bell, professor of professional practice at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and a shortlisted candidate to succeed Alan Rusbridger as Guardian editor, tweeted in response to the Google Trust Project: “Trust is not the problem. Poor journalism is the problem… I don't think trust is a reliable index for good journalism.”

Back to Sambrook: “There is a current push for more ethics in journalism and in training post-Leveson and Savile etc. The NCTJ has put more ethics questions into their exams and we have to ensure students can spot an ethical problem and know what to do about it - but then we always should have done.

“I teach ethics through case studies and pulling them apart. The students enjoy that and it's the most tangible way to teach something that may be a bit theoretical otherwise. I do tell them however that it is likely when they get into a newsroom they will be asked to do something they are uncomfortable about. Most of us have been. We have to decide how serious it is - and before that we have to decide what sort of organisation we want to work for.”

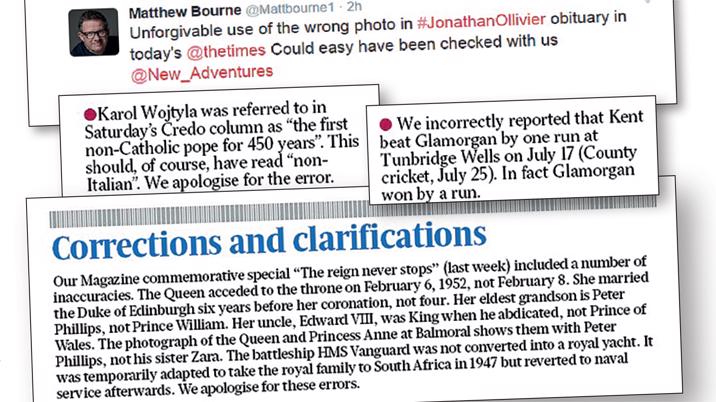

Slanted coverage is only part of the problem; growing workloads and time pressures in what has always been a stressed occupation, coupled with the disappearance of banks of sub-editors have led to a proliferation of the sort of errors that might in the past have cost people their jobs. The Times went through a terrible patch last month that included awarding victory in a first-class cricket match to the wrong side, publishing the wrong photograph with the obituary of the dancer Jonathan Ollivier – this in a paper obsessed with publishing dance pictures almost daily in the news pages – and, the doozy of them all, describing John Paul II as the first “non-Catholic Pope”. To cap that, its Sunday sister managed half a dozen errors in a royal special, including the assertion that Edward VIII was Prince of Wales, rather than King, when he abdicated.

Patrick Kidd, whose role as the Times diarist and now parliamentary sketch writer brings him into close contact with two of the least trusted groups in society says: “The trust thing is interesting. In an age when false ‘facts’ can spread so rapidly on the internet – how many times has someone died before they actually do? – journalists get criticised for being slow or not trustworthy, which is unfair. Look at old issues, there were mistakes galore. What happens now, though, is that mistakes are more easily spotted and owned up to. But people are less willing to trust anyone.”

People are more suspicious of agendas than ever and are able to fact check independently.

Richard Sambrook

Bring back the subs

Fergus Shanahan, who was executive editor at the Sun before he got caught up in Operation Elveden and eventually cleared of any wrongdoing, is less forgiving of the “shocking litany” of Times mistakes. “The reason? Subbing is a dying craft and neither editors nor managements care a fig about subbing anymore. It's inconceivable that such disastrous and humiliating mistakes would have happened at any time when there was proper sub-editing and thorough revision. I guess that not so long ago, just one of those royal clangers would have resulted in a stewards' inquiry but when there are so many shockers in one showpiece feature, the game really is up.”

One interesting aspect of all the court cases that arose from the hacking scandal was the constant emphasis on the efforts made to ensure that stories published were absolutely true – even without recourse to such impeccable sources as the subject’s telephone calls – levels of diligence that may surprise redtop detractors.

“Readers are right to question what they read,” Shanahan says. “But that doesn't mean all hacks are scoundrels any more than all politicians are rogues (and there may even be some honest estate agents).

“Being unpopular tends to go with the territory for hacks in tabloid land. But it's a love-hate relationship, otherwise papers would be selling even fewer copies. Does it matter? Yes. Of course readers should feel able to trust their paper.

“Rule one should always be: Are we sure of the facts?”

Such as, is the Pope a Catholic?