Magazine Giants

This column concerns two very significant, very different figures in American magazines. The second one you may never have heard of. The first you will.

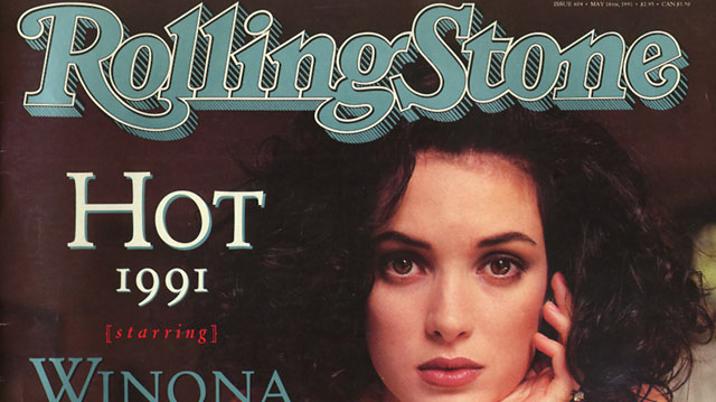

History will record that Jann Wenner, much like his fellow hippies-turned-publishing-moguls Felix Dennis and Tony Elliott, waited a few years too long before selling his big magazine to the money men. At the time of writing, 50% of Rolling Stone is up for sale for a fraction of what it would have fetched back in the early 90s. Back then, it was so full of ads for off-road vehicles, cigarettes and tequila that a carelessly dropped copy could flatten a family pet. Nowadays, you could slip it in your inside pocket and there would be barely a bulge.

Wenner has also left it a bit late to authorise somebody to put his story in a book. He’s already publicly dissociated himself from Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine by Joe Hagan which is currently getting rave reviews all over town for its gleeful depiction of how a short, chubby boy who was uncomfortable with his Jewishness and had not come to terms with the fact that he was gay, turned himself into the Hugh Hefner of the alternative society. It’s a story where somebody is always snorting lines of cocaine from the nearest available surface, at least one of the people in any room will have neglected to put their clothes on and Mick Jagger seems to be always on the phone.

I suspect what rankles most with Wenner about the book is the fact that most of the people he’s dealt with over the last fifty years, from the writers who worked on his magazine to the rock stars his magazine celebrated, don’t appear to have liked him very much. Furthermore, now that Rolling Stone is not the power in the land it once was, they have no compunction about saying so.

Now that the magazine is not what it was, there’s a danger of forgetting what it once was. What the writers, photographers and rock stars don’t fully understand is just how much of a long shot Rolling Stone was and that the fact that it flourished while all the imitators fell by the wayside says a lot about Wenner's tenacity and his ability to live his privileged life as one of the media elite while retaining a sense of how much of it he could transmit to the reader in Moose Droppings, Ohio. His achievement in doing this was far more significant than even the greatest achievements of the biggest names who worked for him. Annie Leibovitz, Hunter S Thompson, Jon Landau and the rest. It was Wenner who made them famous, not the other way round. It’s often that way with editors.

Queen of the Muckrakers

In its November issue in the year 1902 the American monthly magazine McClure's published the first instalment of The History of the Standard Oil Company. This was to be the first of eighteen parts. People had patience in those days. The history didn’t reach its conclusion until the spring of 1904.

It told the story of how oil, which for years had been found in the ground of Pennsylvania, was initially marketed and sold as a patent medicine. It wasn't until the middle of the 19th century that it began to be used as a lubricant in engineering. It wasn't until the late 19th century that the people who had sunk the wells in search of it found ways to refine it further. By then, this exploding market had come to be dominated by one massive company which controlled every aspect of this increasingly rich business by fair means and foul.

The story's publication coincided with a period where many Americans felt a passion for self-improvement and were starting to feel the government needed to do more to control the robber barons of American industrialisation. Even the president, Theodore Roosevelt, relied on the so-called “muck raking” journalists of magazines like McClure’s to set the tone of popular debate.

The author of the Standard Oil story, which was read by McClure’s 300,000 subscribers every month and then read aloud to countless thousands more, was Ida Tarbell. She was in her mid-40s at the time. Tarbell was a former teacher who had made her name writing a hit biography of Abraham Lincoln which made use of the testimony of people who were alive at the time of the Civil War. The Standard Oil story was a classic example of her technique. Massive research, chronological order and unsentimental self-editing. It worked. It did more than capture the national imagination. Six months into its publication in the magazine, her editor called her "the most famous woman in America”. He wasn’t exaggerating.

Ida Tarbell’s monumental story, which was turned into a best-selling book, arguably left a greater legacy than any other piece in the history of magazines. It led Congress to introduce legislation to curb the powers of the monopolies. It ensured the name John D Rockefeller would send a shiver down the ages, summoning pictures of the top-hatted plutocrat which still inhabit the American imagination. Furthermore, it crowned the era when magazines were seen as political weapons.

Could it happen again? There have been bouts of self-improvement throughout human history and it could be we’re due another. Maybe, just maybe, some magazine publisher will think it worth really investing in content if they could have genuine exclusivity on a subject that truly matters to a mass audience the same way oil mattered to Ida Tarbell’s readers? What sort of subject? How about Facebook? It’s overdue an exposé. And one thing you can guarantee about that exposé, it won’t happen on the web. They’ll make sure of that.

One for the road

The Classic Motoring Review is small enough to fit in the glove box of an old Triumph Herald. It has no photographs and won’t take your advertising no matter how hard you try. This magazine is the work of Mark Williams, who cut his teeth on motorcycle magazines like Bike back in the day. His magazine is unashamedly aimed at people who identify strongly with “back in the day”. The first issue from Mark’s Godwyn House Press which is based in rural Wales, is made up of elegies to various aspects of motoring past. Aspects such as delivering the first right hand drive Lamborghini to Britain in 1983 or an interview with Enzo Ferrari from 1977. What they all have in common, I guess, is that they’re all written by highly respected writers such as Richard Williams and Keith Botsford who wouldn’t be asked to write those pieces by any of the established magazines. It’s quarterly and only available on subscription. If you were familiar with the Allman Brothers’ “Jessica” long before it became the theme for Top Gear, you might just like it.

Turning point?

The fall of Harvey Weinstein – and was there ever a fall so steep and sudden – feels like the end of celebrity culture. Weinstein positioned himself at the fulcrum of the central transaction that keeps the star maker machinery going. On one side was an ever rolling stream of ambitious, physically attractive actresses who had to make it in that brief window before the dew was off their beauty. On the other side was a handful of glossy magazine brands which were always in pursuit of the face of whatever year it was to put on their cover, sell more copies, hereby enhancing the perceived glamour of the starlet and possibly even leading to one of those lucrative contracts as the “face of” some beauty brand. The fact that he was finally brought down by the press suggests that some of the people who previously couldn’t imagine themselves ever falling out with Harvey suddenly found they could get by without him. It seems a significant moment for magazines, as well as everything else. Presumably somebody is already working it up into a film.