Rob Orchard is a man on a slow mission. Ever since 2011, when the first issue of ‘Delayed Gratification’ found its way into the consciousness of 400 subscribers, he has focused in on the idea of slow journalism.

“Just like slow food and slow travel, slow journalism is the opposite of this digital world which just has this incredible premium on speed,” he says.

Thoughtful and bookish, and wearing his 43 years well, Orchard runs the operation from his bungalow in Surrey surrounded by a delightful display of all 53 issues of his stylish, bordering on trendy, magazine that he co-edits with university friend Marcus Webb.

He speaks so passionately and eloquently about this lifelong mission so let’s hear it in his own words...

How did it all start?

A: After leaving university, we went off to start our careers [Orchard was editor on Time Out, Dubai], but five of us were back in London in 2010. It was a very bleak media scene by that stage. There was this kind of overwhelming air of despondency in the industry.

Everybody said digital is the future, but nobody had any idea how to make money out of it. Everybody was kind of cutting budgets, cutting members of staff, shrinking aspirations, fewer pages and more invasive advertising.

Just everything was just a bit horrible. And the five of us, we were quite, I think we remain quite — What’s the word? — grand. We’ve just got kind of quite grand visions of what journalism can be still.

And I think what we all thought was, you know, if there’s going to be any value in this, if anybody’s going to make any money out of it, you can’t just cut back, it can’t be a race to the bottom.

We wanted to do it quite idealistically without any advertising or commercial support. So just to have something that was reader funded that could do good journalism.

What is Slow Journalism?

A: If you take your time, you get better results and at the bare minimum, you want journalists to be able to have time to speak to some experts, speak to some people on the ground and hopefully visit. Do some proper research and investigation before they try to give their best first approximation of the truth.

And a lot of journalists weren’t being allowed to do that. Journalists everywhere were on the back foot. Some journalists were being asked to turn out eight stories a day, which just became ridiculous. They had time to top and tail a press release. No time to talk to anybody, it was just constant.

It wasn’t good, it’s not good for society, it’s not good for readers, it’s not good for journalists, it’s not good for anybody.

And the only thing that it’s good for is the matching up of the perverse incentives of this strange digital world that we’ve built where volume and speed is everything.

So, we came up with this idea and we worked away on it in 2010. We sold 400 subscriptions in advance which gave us just enough money to cover costs. Now we’ve got just over 8,000 subscribers, and we’re selling about 3,000 at the newsstand.

What lessons do you think slow journalism has for mainstream media?

A: Newspapers I think is a completely different thing because you’re on that kind of daily schedule and of course you’ve got all those updates to do and it’s a much more transactional thing, news reporting.

In terms of magazines, I suppose the kind of thing that I have found is that there is a niche for a very distinct appetite.

For news with real perspective, actually three months isn’t that long a time to let the dust settle on a story. But our readers really, really appreciate this distance from big stories.

It happens time and time again that some something big happens. A natural disaster, a terrorist attack, a surprising election result. And you get intense coverage of it. For three, four or five days by the rest of the media, almost overwhelming, like 24/7 coverage.

People being interviewed while the disaster is still unfolding. While they’re still on the back foot, well, they’re still kind of stressed out and so on, buildings on fire behind them and their families being taken out of it and they’re talking into the microphone.

What we do is we go back three months later and we try to take a broader view. So, at that stage you’ve got people who’ve actually had time to process what’s going on.

We’ve had time to work out who they think is to blame for it. And you’ve had time to see whether all of the promises that were made in the heat of the moment by the government and by international organisations have actually been fulfilled. Very often, they haven’t and very often this terrible event has now become a political event that is being used for different ends.

An example that jumps to mind is the earthquake in Turkey [February 2023]. Blanket coverage, horrific event. But three months later, nobody’s talking about it except, obviously, in Turkey. Erdogan somehow manages to spin this thing that is a disaster for his regime into a positive and galloped home at the election.

So that sort of whole new level of story is very, very rarely covered.

What about the future?

A: We’re now 13 years in and I feel that we are able to do some kind of bolder stuff and spend some more money on marketing to try to reach out more.

We will have a new app because our digital provision isn’t that great. We may also look at video and audio content. We’re doing advertising in Private Eye and some ads on the tube.

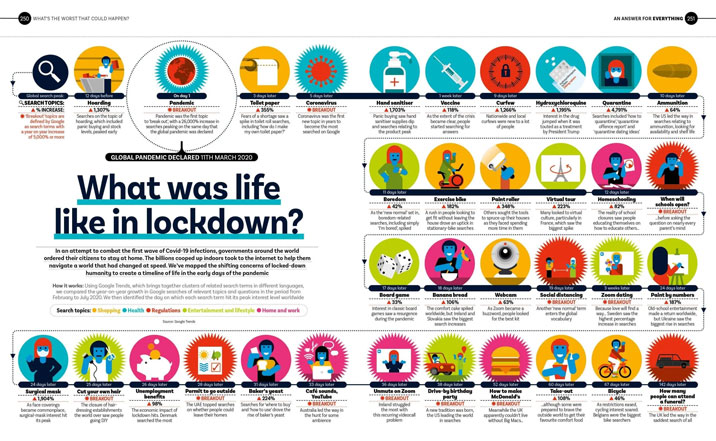

We’ve always been big on infographics. We got a commission a few years ago to do a book of the graphics and we’ve got a new book coming out with Bloomsbury this year.

I’ve got a mortgage that doesn’t end until I’m 70. So, I’m gonna have to keep working to pay for it!

Review: Delayed Gratification — ‘Last to breaking news’

Issue 53 of the Slow Journalism Magazine is 124 pages of snazzily designed, cleverly illustrated non-stop homage to the movement that uses the tagline ‘Last to breaking news’.

As if to emphasise the point to any new readers who might come across it on the newsstand, the editors write: “We can provide perspective to make sense of why things are happening. We can give you all sides of the story. And while negativity may drive news consumption online our magazine doesn’t need to lean on sensationalism and outrage to get clicks.”

Hostages in Gaza, indigenous unrest in Australia, China’s Belt and Road initiative, Sam Bankman-Fried, riots in Dublin and ‘the downsides of Mexico’s avocado trade’ all get the slow treatment and emphasise the global approach of the home-counties produced magazine.

There is also a change of pace — denoted ‘frivolous’ with an asterisk in the contents — looking at movies, the back story to the Beatles AI hit ‘Now and Then’ and ‘That’s Entertainment’, which takes an, er, entertaining look at showbusiness with beautifully crafted graphics.

There is no advertising and just one page of promotion for their online shop so there is full-on value for the £12 cover price, which is admittedly among the steepest on the newsstand.

Editor Rob Orchard is proud of the commitment. “It’s brilliant print quality, amazing kind of tactile paper, long-form journalism that’s properly invested in and beautifully designed,” he says. “All the stuff that makes you know what’s still important for all that we’re still enthralled with smartphones in this digital world.”

Fact-Based Journalism

Yup, ‘fact-based journalism’ really is a thing as well, with its origins firmly rooted in Donald Trump’s reign of terror with ‘fake news’.

High profile media outlets like the Associated Press, ProPublica and even the US Agency for International Development use the term to suggest a differentiation from Regular Joe journalism.

Academics from the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy in North Carolina crunched the numbers and found that as the Trump era ushered in the strategy of politicians slandering legitimate reporting as ‘fake news’, self-identifying as ‘fact-based journalism’ became a way for news organisations to push back against efforts by politicians or hyperpartisan media outlets to discredit them.

Report author Prof Philip Napoli acknowledges that while there may be compelling reasons to embrace the term ‘fact-based journalism,’ doing so represents a damaging concession. “To describe one form of journalism as ‘fact-based’ is to tacitly acknowledge that there is also such a thing as ‘non-fact-based journalism.’ And there isn’t,” he says.

“All journalism is fact-based. If it’s not, then it’s not journalism.”

But this one looks like it might run and run. “If some sort of qualifier is indeed necessary in this age of widespread efforts to disguise falsity and political influence operations as journalism, then how about a term that goes on the offensive — perhaps ‘legitimate journalism’ or ‘authentic journalism’? Such terms better distinguish organisations that are producing journalism from those that are making a mockery of it.”

So, in the UK’s post-apocalyptic, post-election world, I’ll be doing my bit for legitimate, authentic, genuine, reality-grounded journalism. Or maybe I’ll just continue to tell it how it is. You, too?

Coming next time: ‘Constructive Journalism’, another movement Dr Alan Geere has tried to embrace in a 50-year career across newspapers, magazines, international media development and academia.

This article was first published in InPublishing magazine. If you would like to be added to the free mailing list to receive the magazine, please register here.