If I asked you to draw a self-portrait what would you do? Find a mirror maybe, or think about how you feel and try to put that down on paper? You could interpret it in various ways, all valid, because humans understand the meaning of the request. Ask AI for a self-portrait and it gives you back a Rembrandt or a Van Gogh. Because those, it finds, seem to be the images most associated with ‘self-portrait’. The true meaning of the term eludes it because it is still a long way from general AI – as I said in my last column on AI words. But what can narrow AI do in images and what does it mean for publishers or artists?

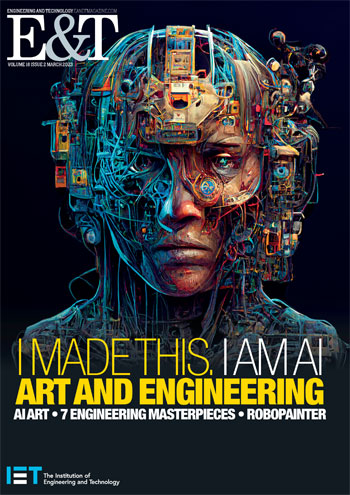

Our February issue special on art and engineering had our first cover generated by AI and, although there to illustrate the AI, I’m sure it won’t be the last. It took many attempts trying out various sets of keywords in different AI art bots. And, of course, we failed to get it to paint a self-portrait.

Those fearful of AI will be worried and cheered in equal measure by the results. On the one hand, there are those who fear AI taking jobs from humans. Magazines, especially those for the creative industries, are already declaring they won’t use AI art. Their fear is it will dehumanise the work and put professional creatives out of business. Others see it as just another tool for ideas and technique: a starting point or an interesting place to explore ideas.

Today, it depends on the degree of creativity and art in the application. It can do a quick illustration for a presentation. It might manage an illustration good enough for a magazine and it can match any requirement you could dream up, going way beyond the range of the vast picture libraries. And it is only going to get better. Eventually, the art may be more in the human input than the machine output. Humans will learn to work it better too. But if you want real art… it’s got some way to go.

Type in a subject, style or famous artist – or more than one of each – and these bots seem to make a reasonable attempt at fulfilling the request. Even with my limited art knowledge, I can see that it’s aping certain characteristics of a school or an artist but often misses what made them great. Nevertheless, the results are convincing and fun.

There are several problems with AI art as it is today.

This artist’s teacher is existing data. It reproduces and often magnifies stereotypes, cliches, biases and prejudices. We found, for example, it reproduces stereotypes for ‘engineer’: mainly males, mostly white, wearing hard hats and holding building plans. To avoid those, you have to spell out what to avoid.

The ‘community showcase’ in Midjourney is a giveaway of the people using this site, the sources it’s tapping into, or perhaps both. Yes, welcome to the weird fantasy worlds of teenage boys who don’t get out enough. There’s invisibility cloaks and alien planets, but mostly impossibly shaped young women in skin-tight futuristic fantasy costumes holding laser guns. And, to be fair, there’s a few kittens as well. It feels like we’ve seen it all before, because we have.

But those problems will be resolved in time. AI has a future in quick and cheap graphics and illustration. It will find a market if it can’t be got for copyright infringement. AI’s yet to be in court but copyright only holds for a specific form of words or image; you can’t copyright an idea. AI uses typical elements it finds in common use; as Ed Sheeran proved in his defence against the Marvin Gaye estate, commonly-used building blocks are not original works protected by law. Watch this legal space.

Lacks the human touch

AI ‘art’ is useful but is it really ‘Art’ in a meaningful way, rather than just pretty, striking, silly or mildly amusing pictures? Proper art is about originality as well as creativity. We want to hear, see or feel the beauty of the next great thing to come from real people – not a machine’s version of the last.

What’s the point in a pretend Picasso 100 years on, a da Vinci look-alike 500 years later or in writing another Beatles-like song 60 years on? The Beatles always moved on, incorporating new influences in unexpected ways, and it’s what kept them interesting. Who knows what they would sound like now? AI can only guess.

To hear a song that sounds like the 1960s Beatles from a machine is even less interesting than from a real band. Oasis were derivative for sure, but they also added something that was very much their own. Perhaps humans can’t help being creative, while AI finds it hard.

Even if AI could manage it, human bias may deny it proper credit. People actually quite like other people to make things for them. It might be illogical, but it feels more ‘authentic’. If AI is winning art competitions, that may say more about the competitions than AI. And when it’s found out, it’s considered cheating.

We’re fine with AI in the background, like algorithms to suggest our TV, or match reports or useful graphics. But AI generated works like songs, images or writing arrive with a great fanfare and so far have then sunk without trace.

AI art will grow into a role for sure. When synthesisers came along, musicians feared they’d be put out of jobs and unions resisted. 50 years later, that protest seems quaint. Now we have programmed electronic music. We still have music played on instruments by real people. And we have everything in between. Music is richer for it. Interestingly though, even for pure electronic music, people still turn up to the live gig to see the human element behind it, even if it’s just a producer with a laptop. People tend to like people to tell their stories, perform their songs and paint their pictures.

AI will change creatives’ jobs for sure but it’s not quite all over for humans yet.

This article was first published in InPublishing magazine. If you would like to be added to the free mailing list to receive the magazine, please register here.