Nearly two years have passed since an edict from the English Football League placed one of the game’s oldest matchday rituals under threat.

A vote at the EFL’s annual general meeting on 8th June 2018, determined that the 72 member clubs would no longer be obliged to print a programme for every home fixture.

The proliferation of digital media, along with declining sales and rising costs, were cited as reasons.

As a result, the governing body agreed to revise commercial arrangements which made publication mandatory and clubs in the Championship, League One and League Two were given the freedom to make their own judgements on a match-by-match basis.

Of course, football fans have been reluctantly forced to accept dispensing with tradition before.

Unsociable kick-off times, the iron grip of TV companies and a seismic shift in clubs’ commercial priorities have put paid to many habits and routines that had filtered down through generations of supporters.

Programmes are an intrinsic part of matchday. Stopping at a programme kiosk on approach to the stadium has become second nature to many. Much like purchasing an over-priced pie before kick-off.

The EFL ruling, traditionalists felt, signalled the final whistle. If one club pulled the plug, others would soon follow.

Stevenage took the bold step last August of becoming England’s first professional club to offer a digital-only matchday read.

Their League Two counterparts Colchester United adopted a less drastic and far more novel approach by giving supporters a printed copy as part of their ticket.

However, the anticipated domino effect has yet to take hold and football programmes are pressing ahead in the battle to evolve.

The biggest challenge, perhaps, is that they are no longer a club’s primary method of communication.

When programmes were introduced in the late 19th Century, their purpose was providing the team line-ups and a space for fans to note the result and goal scorers.

After the Second World War, they became a lucrative revenue stream through advertising and developed into a way of engaging with fans through manager columns, player interviews and statistics.

With the saturation of media coverage, both online and through dedicated 24-hour sports news channels, that is no longer the case.

“I'm not sure how many people actually read the content of a programme,” says Roy Gilfoyle, chief sub editor at Reach Sport, who publish the official matchday programmes of Manchester United, Liverpool, Everton, Tottenham Hotspur, Chelsea and Celtic.

“It is a painful thought for those who slave over making them as interesting and as accurate as they can be – but I know many people who buy a programme purely as a memento of a game.”

The biggest challenge, perhaps, is that they are no longer a club’s primary method of communication.

Less time to talk

At the game’s top table, it is not so much the direct impact of digital’s stranglehold over print that creates headaches for programme editors in their quest for captivating and original content.

A by-product of increased demand from more far-reaching, instantaneous and, indeed, lucrative platforms has put a strain on the time and headspace afforded by managers and players.

A typical week’s media duties for a Premier League manager, for example, will consist of an interview with his club’s in-house media team and separate press conferences for TV, radio and written media.

Ahead of a live TV game, a one-to-one interview for the broadcaster’s preview show is often factored in too.

And let’s not forget international rights holders and separate briefings for Sunday newspapers, depending on the day of the fixture.

Very little, if any, original material is left for the matchday programme.

In yesteryear, the manager’s programme notes were compulsive and often explosive reading. Like a fortnightly ‘state of the nation’ address.

One-to-ones between editor and manager are now a rare beast. Many clubs instead construct a column using quotes adapted from the pre-match press conference.

The opening words to Wolverhampton Wanderers’ programme are emblematic of head coach Nuno Espírito Santo’s attitude towards media duties.

His proclamations rarely amount to more than five paragraphs.

Paul Lambert, one of seven full-time managers I worked with in my time at Aston Villa, had a bizarre ban on praising individuals in his column. It was never a captivating read.

Player exclusives too are less frequent. Instead, their time is monopolised by TV and sponsor demands.

Making it special

Little wonder, then, that the target audience of a programme is, more than ever, the collector and the souvenir hunter.

The blurred lines of what can pass for a ‘special edition’ – traditionally reserved for prestige fixtures and major anniversaries – have also been redrawn.

“Nowadays, every anniversary or special occasion is seized upon to provide an opportunity to make that edition stand out from the rest,” says Gilfoyle.

“I remember Liverpool producing a special cover and inside content to mark 100 years since Bill Shankly’s birth.

“Each club have their own occasions and half the battle is looking into the future to spy opportunities to make an edition special in some way.

“Programmes may not be cheap but they are certainly cheaper than most other items at a club shop that might bear the club names and date of a particular fixture. And you can't underestimate the determination of a collector.”

The pursuit of new hooks, no matter how tenuous, is understandable when anecdotal evidence points to a decline in sales.

Not only are programmes competing with the digital age, the inconsistency of kick-off times has wreaked havoc with supporters’ matchday routines and, in turn, their purchasing habits.

In some respects, these challenges provide a catalyst for innovation, through ground-breaking design and the ability to marry print with the latest technologies.

Forward-thinking non-league side Frickley Athletic became the first club to find success with Augmented Reality (AR), enabling fans to unlock digital content such as videos and stats by hovering their smartphones over a particular page.

The ‘Pokémon-Go’-inspired enhancement has since been adopted by a host of Football League clubs.

And, naturally, there’s a greater emphasis on aesthetic. Wolverhampton Wanderers captured the imagination of supporters on their return to the Premier League with a series of front covers created by local artist Louise Cobbald.

Her stunning compositions were created using watercolours and the original artworks were auctioned off for charity.

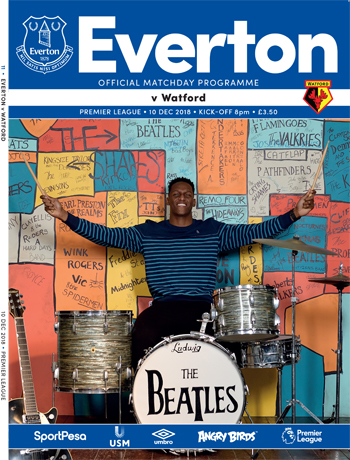

Meanwhile, Everton’s programme – which bucked a national trend last term with a 9.3 per cent year-on-year sales increase – provided a talking point among Goodison Park loyalists with its striking cover photography.

Adorning the front were images of the Toffees’ star players at Merseyside landmarks, including André Gomes at the Albert Dock, Gylfi Sigurdsson next to the statue of club legend Dixie Dean and Yerry Mina playing drums at The Beatles museum.

A moment to treasure

A favourite initiative from my two-year stint as editor of Aston Villa’s Villa News & Record publication was enlisting lifelong claret and blues supporter and author of the Jack Reacher novels, Lee Child, as a guest editor.

From his Manhattan apartment, the multi-million selling writer contributed several pieces, including an editor’s column, a feature on his penchant for using the names of Villa players in his books and a Q&A with legendary midfielder Gordon Cowans.

The front cover also mimicked one of Child’s best-sellers.

“I have a great job and it has brought me many opportunities,” Child wrote in the 16th January 2016 edition for Villa’s Premier League fixture against Leicester City.

“I have met President Clinton and President Obama. Tom Cruise flew me in his helicopter. I have had dinner with kings, lords, sirs and Oscar-winning actresses.

“I have watched the Boston Red Sox with Stephen King. I have thrown out the ceremonial first pitch at Yankee Stadium.

“But best of all was an invitation to meet Gordon Cowans at Villa Park.

“I treasure the memory, because I think he was the best player we have ever had – a truly world-class talent – and no Villan gave me more pleasure to watch. I was glad to get the chance to tell him that.

“So, when I had to pick a player for a Q&A, naturally I chose him, and I'm grateful he agreed to respond.”

In yesteryear, the manager’s programme notes were compulsive and often explosive reading.

Programme of the Year

Every season, Programme Monthly and Football Collectible – a long-running magazine for programme enthusiasts – awards a Programme of the Year title to clubs in each of English football’s top four divisions.

Brighton and Bournemouth shared the honours in the Premier League last season, while West Bromwich Albion, Coventry City and Exeter City came out on top in the Championship, League One and League Two respectively.

While judging is carried out by so-called ‘traditionalists’ – collectors, historians and statisticians – innovation is viewed as a critical component.

“Obviously articles that appeal to those groups – such as the historical stuff - are really going to work well,” explains Paul Matz, the magazine’s editor.

“But the areas that generally score well are innovation and doing things slightly different from the rest of the pack.

“Lots of clubs have been innovative. Southampton, for example, moved to an A4 sized programme a few seasons ago – which wasn’t something collectors liked because it doesn’t make them easy to collect. They also charged a fiver, which was a big price increase.

“But it gave them greater scope to produce different types of features that wouldn’t work in the traditional B5 format.

“Innovation is important to programmes maintaining their buyability in the future.”

So, with football’s priorities rapidly shifting, for how much longer will matchday programmes retain a place in hearts and minds?

“Sales may be struggling in general but I think there will always be a place for programmes for as long as the game is popular,” Gilfoyle concludes.

“Clubs have tried to get digital programmes off the ground but I've never seen those as something that could satisfy consumers in the long-term.

“People get programmes more for the memories they can bring back in 10, 20 or even 50 years’ time.”

Innovation is important to programmes maintaining their buyability in the future.

This article was first published in InPublishing magazine. If you would like to be added to the free mailing list, please register here.